Confetti cannons blast colorful debris into the sky. In a sold-out arena, fans are dancing and singing at the top of their lungs. Pitbull, dressed in his iconic snow-white blazer and sunglasses, begins his last song of the night as I ask myself, Would today have been a good day to die?

The night isn’t over, but as I look at my date dancing beside me, I know my answer. Today would have been a good day to die. My date was ecstatic because she got to see one of her favorite performers from the 10th row. (When I texted her to ask if she wanted to come with me, her reply included six crying-face emojis, three shocked-face emojis and seven exclamation points.) And I was happy because I also got to see Enrique Iglesias perform live—someone I grew up listening to in the backseat of my mom’s car.

JASU HU

Before I continue, I should mention that I’m not depressed. I’m not suicidal. And no, I don’t normally ask myself this sort of thing at concerts. I’m asking because I’ve committed to more self-reflection. I’m actually terrified of dying, and therein lies the point.

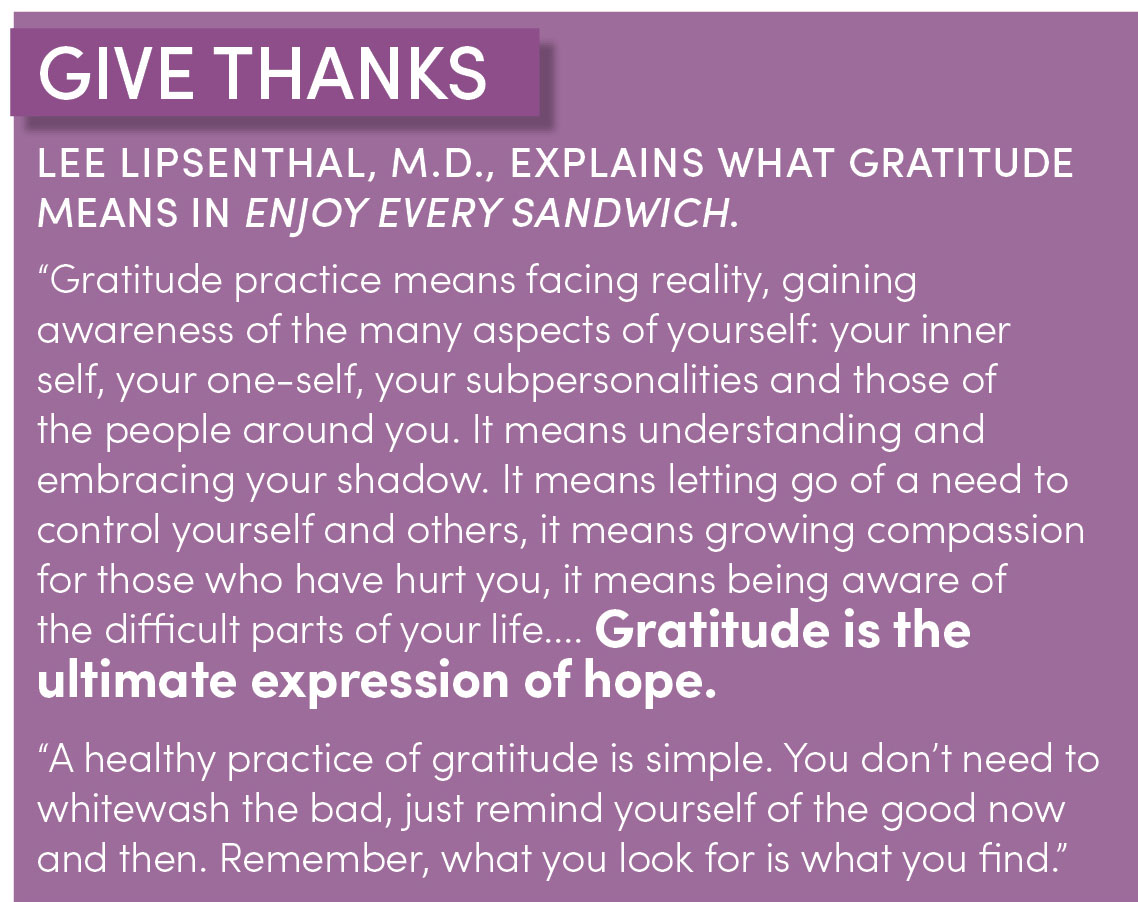

This self-reflection, like most self-reflection, was inspired by a book, in my particular case, Enjoy Every Sandwich: Living Each Day As If It Were Your Last by the late Lee Lipsenthal, M.D., who served as medical director of the San Francisco area-based Preventive Medicine Research Institute. Throughout his career, Lipsenthal observed hundreds of patients overcome their fear of death and find ways to live with joy despite their illnesses.

In 2009 Lipsenthal was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, forcing him to test his own teachings. In his book, he shares the story of his experience with cancer and the techniques he used to manage it, such as meditation and practicing gratitude. “On this path I learned that if my life was full each day,” Lipsenthal writes, “if I enjoyed the people I was with, if I consciously took time to love my family, if I did work that fed my soul, that day would be a good day to die. Nothing more would be needed.”

Related: A Good Life Contains These 6 Essentials

To track my days, I will record what I do each day in another book, a journal I’ve kept for more than a year. It had been gifted to me by an ex-girlfriend with a card about making the most out of each day. I tend to write just a few incomplete sentences about my day each night, but it’s interesting to look back and see what I did the year prior. Some entries are entertaining (“went to the bar with some friends. Tonight was lit” written in a buzzed chicken scratch), while others are much more mundane (“worked; ran 4 miles; watched baseball”). But now in addition to journaling about my days, I’ll keep a mental scoreboard of the good days and the bad ones. If you’re hitting golf balls on a driving range, you don’t quit after dribbling a shot 10 feet in front of you—you look for one to end on, a perfect shot. This is my new daily standard.

Settling into bed after an incredible concert with a new friend, I’m one for one.

***

The next morning, my alarm goes off sooner than I would prefer on a Saturday. I didn’t get home from the concert until 1:30 a.m., and even though I’d rather sleep in, I promised a friend I would help him and his fiancée move into their new apartment. So with a bit of reluctance, I get out of bed and drive to their new home.

We have no control over when or how we die, but we can control how we live each day.

The move takes seven hours and involves heaving the contents of two U-Haul trucks up three flights of stairs in mid-90s heat. In the process, I also skin my left leg trying to break the fall of a bedside table I thought I was strong enough to lift by myself. Once we’re done, I come home and promptly fall asleep.

With my batteries recharged after a quick nap and long shower, I head to my parents’ place for dinner before meeting my friend Christian to watch our friends Nick and Olan and their band Monoculture play a show in downtown Dallas. After paying for my ticket, Olan promptly greets me and thanks me for coming. I’ve seen them play at least a dozen shows by now, but each time Olan is extremely grateful for the support. After their set, I stick around for the following band before heading home.

As I walk upstairs to my apartment, I take inventory of my day. I helped a friend move, I spent some time with my family, and I supported a couple more friends in their passion to play music. All in all, not a bad day. Would today have been a good day to die? Definitely.

JASU HU

In the middle of the night, I wake up to go to the bathroom, and in a half-asleep state, I type the following note on my phone: “In order to be satisfied with my day, I need to fulfill certain aspects of my life. A day well-spent includes a personal challenge like getting a good workout in, professional satisfaction and spending time with loved ones.”

Related: 7 Things I Would Do on My Perfect Day

When I wake up in the morning, I’m completely puzzled. Aren’t some days just… days? How am I going to meet my criteria every day?

***

The next few rotations of the Earth aren’t particularly memorable. My memory book is filled with a lot of “work, gym, watched baseball, read” entries. They aren’t bad days. They are just normal days, devoid of anything particularly exciting. Would I be OK with dying on these days? I suppose so. Would I prefer my last day to be more eventful than a routine, the enjoyment of which hinges on the Texas Rangers’ bullpen? Yes.

I eventually get a break from the monotony later in the week. My friend Chris invites me to a happy hour with his co-workers, and in need of a break from the usual, I happily oblige.

Sitting on the patio under the close-to-unbearable heat of the Texas sun, I order a beer and start introducing myself. As I exchange names with those sitting around the table in mismatched lawn chairs, one girl in particular catches my eye (we’ll call her Sarah). I’m not sure what exactly about her captivates me (perhaps her pink lipstick or her mysterious eyes), but I just know that I’m attracted to her. I quickly learn that this isn’t Sarah’s office happy hour either; she’s just along for the ride.

My beer gives me just enough courage to talk to Sarah more. We exchange basic résumé items like where we went to college, where we grew up and what we do for a living. We find out that were it not for my last-minute decision, we would have gone to the same school. Under the spell of a second drink, I start padding my résumé. I tell her about my most recent half marathon (she’s a runner, too). I also tell her about the scar under my left eye, and how it’s from the nine stitches got I after a fight in an indoor soccer match (it was really just a reckless tackle, but a fight sounds cooler).

As the night goes on, I realize it’s now been several hours, and we’re still talking. It’s getting late, and as much as I’d like to stay out, I’ve had plenty to drink. And there’s work in the morning. Heading home in the backseat of a Dodge Journey driven by a stranger named Tun, I look out the window and replay snippets of the conversation with Sarah in my head. Would today have been a good day to die?

***

After hitting snooze a couple of times the next morning, I force myself to get out of bed. My head is pounding, I’m nauseous, and I desperately need water. I immediately realize that just because this exercise is supposed to encourage me make the most of my days, that doesn’t mean I need to drink like it’s my last day on the planet. I’m very hungover, and although I’d much rather sit at home all day Netflixing and nursing gallons of cucumber-lime flavored Gatorade through a straw, I need to get to work.

I don’t accomplish as much as I’d like to at work. I stick to mindless tasks rather than the tasks that require more brainpower. My exciting night turns into one of those all-day hangovers that looms over you like a cloud of regret. I spend that night eating dinner, watching baseball and sipping water. Before I go to bed, I make my daily journal entry and ask myself, Would today have been a good day to die? It’s the first day I answer with no. What a waste.

As the month progresses, I notice a pattern of the mundane being broken up by the exciting nights when I actually have plans. I haven’t given much thought to whether I’m checking off my self-imposed criteria for what could be considered a good day, but rather I’m simply recapping my days and deciding if they were well spent.

Related: 39 Tips to Have the Best Day Ever

During the month, I see Tears for Fears and Hall & Oates play a doubleheader concert with my uncle. I take my dad to see his alma mater play soccer. I also have a reunion with six of my best friends from high school.

These days are special. My uncle had always wanted to see Tears for Fears perform, and I help him check that off of his bucket list. The soccer match is special because the first time my dad took me to a game, he splurged on front-row seats behind the bench. This time around, I treat my dad, and I splurge on seats behind the bench, too. And at my mini-reunion with my high school friends, several we-need-to-hang-out-mores are exchanged. The sentiments are not the kind you say to that classmate you’re kind of glad you lost touch with, but the real kind—the kind you genuinely mean. All great days to die on.

JASU HU

But I begin to realize that even though these were moments I’m thankful for, in some ways I’m just checking things off of a to-do list. I ask myself if I’m really relishing these experiences or just filling my schedule.

After his diagnosis, Lipsenthal writes that he began to appreciate the time he spent with his loved ones more than before. With his odds of survival at less than 10 percent, he realized that any interaction with a friend, colleague or family member could be his last. “I no longer have a bucket list,” writes Lipsenthal. “I have love in my life. This is far greater than seeing the Pyramids, climbing mountains, eating Thai food in Thailand, or any other physical activity that might be fun to experience. I am loved and I have loved. My bucket list is complete.”

***

I live within walking distance of what is billed as the best Fourth of July fireworks show in North Texas (doesn’t every fireworks show say that, though?), so I decide to throw a pre-party at my apartment.

Around 3 p.m. on the eve of the Fourth, I start grilling hamburgers and hot dogs, set out some drinks and snacks, and pace around my apartment wondering who will come. Slowly my friends start trickling in, first Chris, then Moe and Marina, the couple I helped move, then a few more. Before I know it, I’ve run out of hamburgers and hot dogs, and there are more than 20 people crammed into my 982-square-foot apartment.

After the sun sets, we all march out of my apartment and head up to the rooftop of the parking garage for a perfect vantage point to see the fireworks. At some point during the show, I catch myself drifting away from the multicolored explosions lighting up the night sky. Instead I slowly scan those around me—college friends, high school friends, work friends, friends of friends, a couple of my cousins and an uncle—and I smile. Would today have been a good day to die? Surrounded by people whom I love and who love me? Definitely.

Related: The Secret to Happiness Is Just Love

The following day, the actual Fourth of July, I treat my family to a hearty breakfast, and they treat me to a savory afternoon barbecue. In the evening, my roommate and I have tickets for a Rangers game. I think about how this has the makings of a great day. What better way to celebrate America’s independence than by gorging on delicious food and watching baseball?

But as the game progresses, I realize I’m not having a good time. The Rangers are losing. It’s 92 degrees outside, but the humidity makes it feel like 100, and even though there are fireworks after the game, the thought of fighting through traffic as more than 40,000 people try to exit the ballpark agitates me. So after sweating it out for six innings, I ask my roommate if he’s OK with leaving after “God Bless America” in the middle of the seventh inning. I drove, so he doesn’t have much of choice, but he reluctantly says it’s fine.

After my nightly journaling, I think about whether this would have been a good day to die. No. Well, kind of. I enjoyed the part of my day when I ate great food with my family. But I didn’t enjoy watching my team lose while sweating through my shirt and shorts. Another no.

***

In his book, Lipsenthal writes about how embracing a positive attitude helped him when he had cancer. A positive mindset allowed him to enjoy life more, rather than making excuses about how his life could be better, the way a pessimist or a perfectionist might. “ ‘Yes, but… ’ is their language,” he writes. “They can’t enjoy a sandwich because it has too much mayonnaise or too little lettuce or the bread is too hard or too soft.” This makes me think about the Rangers game. It was sold out. Thousands of people wanted to be there. Was I the only one who didn’t enjoy it? I wonder. Why wasn’t I more thankful for that evening at the ballpark?

Throughout the book, Lipsenthal uses the sandwich as a metaphor for life. He writes that the two parts of a sandwich are love and gratitude. “Relationships [love] are always the main ingredients of most people’s sandwiches,” he writes, “And you could say that gratitude is the bread that holds it all together.”

I have the love part down—friends and family I love, who love me. But if I’m not truly grateful for my experiences and the time I share with those I love, am I really enjoying every bite of my sandwich?

Related: 5 Ways to Be More Grateful on the Daily

Lipsenthal writes that he spent much of his life making an effort to be more thankful. For more than 20 years, he would think about what he was thankful for in the morning, and write those things down at night. In the final week of my experiment, I decide that in addition to writing down in my memory book what I did that day, I will also write down at least one thing I’m thankful for. When you practice gratitude, Lipsenthal writes, “You begin to look for things to write each day and instead of looking for things that are wrong in the world, you start focusing on the things that are right.”

***

Asking yourself if you’re OK with dying at the end of every day is a peculiar exercise. This is mostly because death is something no one likes to talk about, but the reality is that it surrounds us every day.

“At any moment, in an instant, life as we know it can change,” Lipsenthal writes. “Our mortality waits for us, sometimes patiently, sometimes not so patiently. But it is always there, undeniable and closer than any of us wants to admit.”

JASU HU

There’s nothing wrong with the occasional reminder that we live on borrowed time. But for me, the experiment was an even more important reminder to constantly question how I’m living my life.

In the month I complete this exercise, I’m lucky to have only two truly bad days—days I thought would not have been good days to die. I had 15 great days and the rest were “meh,” with one undecided.

But I learn toward the end of my experiment that on the days when I looked for something to be thankful for, my meh days weren’t so meh at all. Those days felt fuller—not because I was checking things off of my schedule, but because I was taking time to appreciate them. I might not have done much outside of work on those days, but I was thankful I pushed myself to run an extra mile or that I found a good book to read.

By being mindful of the things I was thankful for, my mindset shifted. Suddenly, going to the ballpark to watch the Rangers play in 100-degree heat wasn’t so miserable. Watching them lose wasn’t so bad either.

Maybe keeping a gratitude journal isn’t your thing. Maybe it’s meditation or prayer. The key is finding what works for you—something to help you slow down, think and be thankful.

“Our mortality waits for us, sometimes patiently, sometimes not so patiently. But it is always there, undeniable and closer than any of us wants to admit.”

We have no control over when or how we die, but we can control how we live each day. We might not always have the opportunity to live each day to its fullest, but if we find things to be thankful for, then each day has the potential to be a good day.

***

The final day of my experiment begins at Terminal D of Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, waiting for my aunt and cousin, who are visiting for the weekend, to arrive from Mexico. After picking them up, I get an outfit fitted for my best friend’s wedding, and then go to another cousin’s pool party. It’s a busy day, which is how I prefer them. As it winds down, I’m watching my 11-year-old cousin and my 20-year-old brother play video games. In the middle of playing, my brother randomly tells my cousin to bring over a photo album on his bookshelf.

Together, we flip through the album, laughing at the younger versions of ourselves. My cousin goes into a laughing fit when he finds a picture of my brother as a (fat) baby, saying he looked like two babies combined. As our laughter grows with each baby picture, I think about the last lines of Lipsenthal’s book.

“Someday you will face your own mortality. At that moment, I hope you see your life has been well led, that you hold no regrets, and that you have loved well. On that day, I hope that for you, it had become a good day to die.”

Now if only the Rangers could win a World Series, then I could really die happy.

Related: 17 Quotes About Living a Beautiful Life

This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.