He looks like an excited little boy.

Sitting on the balcony of an upper-level suite at AT&T Park, Joel Osteen is staring out at the field—the home of the San Francisco Giants—but he isn’t watching baseball. He’s watching the construction of a stage. He’s watching the lights move into place. And he’s watching a series of expensive high-definition cameras finally going up on the massive dollies stationed around the infield. A breeze rolls in off the bay, and the late summer sun burns away some of the morning fog.

“Isn’t that a great shot?” Osteen asks, looking at the signal from one of the panning cameras. In one slow sweep, the cameraman has captured the picturesque bay behind the stadium, the thousands of seats they expect to be filled a day from now, and finally the LED-covered stage where Osteen will stand and preach.

“What is that going to say when that pans toward me?” he asks. “It says, ‘Let’s listen to him!’ It gets people’s attention. It’s the psychology of it. We played with that for a long time to put it right on that level.”

BOB ADLER

Osteen and his team of nearly 200 are in San Francisco for an event they call A Night of Hope. Most of the people working for him traveled together from Houston, where Osteen is the senior pastor at Lakewood Church, a nondenominational megachurch that gathers in the arena formerly known as the Compaq Center, where the Houston Rockets used to play. Tens of thousands attend his church every week, and millions more watch him on televisions around the world, making him easily the most popular preacher on the planet. His broad appeal means personalities ranging from Oprah Winfrey and John McCain to Khloe Kardashian have declared themselves fans. Osteen is also a best-seller machine, one of the biggest names in publishing. (His new book, The Power of I Am

In addition to all that, Osteen and his wife, Victoria, do live events. They’ve held roughly 150 in all, including a handful of packed-stadium special events like the one he’s preparing for here. This three-day affair includes dozens of volunteers doing charity work in the local community, building houses or giving food to homeless people. The main event, on Saturday night, is part old-fashioned revival, part epic Christian rock concert. In the last few years, he’s had similar events pack Yankee Stadium and Dodger Stadium to their respective brims. This is the Friday afternoon setup, something of a ritual for Osteen and his crew.

Soon he’s walking across the infield, toward the complex network of stages erected just behind the pitcher’s mound. There’s the main stage, where Osteen, Victoria and a number of guests will be preaching. There’s also a taller stage behind that, for the dozen or so musicians and their instruments. Most crew members wear skinny jeans, and a few are sipping from coffee cups. The entire arrangement, though, would rival any Pink Floyd road show.

Osteen is heavily involved with preproduction. Even after all of these shows, he’s still excited to see the booms, jibs and cranes. He has fun figuring out where the cameras go, like putting together a puzzle. A man walks slowly back and forth across the stage so Osteen can see how it looks on-screen. In the middle of the outfield, behind the stage, stand three tall LED screens that look as if they’re placed randomly until you see a close-up of the stage with those bright lights filling in the background.

“See, it all lines up,” Osteen says, his characteristically soft, gentle voice barely audible amid the sound of hammering echoing around the park. “We want there to be full, rich shots. We’ll have 30,000 people here with us, but most people will be watching on television. Most people are only gonna see those 40 inches.”

Production value is of utter importance to Osteen. “It’s got to look good, and you’ve got to be precise. There’s so much competing for the viewer’s attention these days. If you’re not prepared with what you’re gonna say, or it’s not relevant, or if something’s just not up to par—even if it’s in focus, but it’s not good lighting, or the sound is echo-y—you risk losing people.”

This dedication to a glossy, attractive final product—to “those 40 inches”—is part of the formula for Osteen’s success. There’s also his eternally positive message. He’s often called “the smiling preacher,” and he intentionally avoids using words like Hell or sin. He never says “Satan” or “evil,” instead preferring expressions like “the enemy,” which could mean any challenge, from an intense crisis of faith to mere self-doubt. Osteen is a motivational speaker with a religious bent, which makes him highly accessible and also a target for criticism.

He also comes across—both in person and on-screen—as genuine, a word most people wouldn’t associate with televangelists. At 52, he still seems like the awkward, fresh-faced preacher’s kid. He frets about how badly he talks sometimes. He incorporates his whole family into the ministry. As a policy, he never asks for money, although in his words, “We’re obviously blessed, and blessed with the ability to be generous and bless others.” He says he just wants to make people happy. He wants to deliver the gift of warm feelings. And every day he seems truly surprised by the way life has unfolded.

***

Osteen’s parents, John and Dodie, in 1959 started their church in an abandoned feed lot, with only a few dozen people. Initially they were Baptists, but soon the church became independent, nondenominational. John and Dodie built it over four decades, and when Joel quit college in 1982, he came back and told his parents that he wanted to start a television ministry. And that’s what he did: He created a production team to broadcast his father’s sermons on TV.

For 17 years, Joel worked on making his father look good. He would take the 40-minute sermons and cut them down to 25. He checked the lighting, the sound, everything down to picking out his father’s suits and ties. And it made him happy. His father was his best friend, and he loved working and traveling the world with him.

Osteen is a motivational speaker with a religious bent, which makes him highly accessible but also a target for criticism.

“That’s all I thought I’d do with my life,” Osteen says. “I was content.”

Once in a while, John would prod his son. “Joel,” he’d say. “Why don’t you come up here and help me pastor the church? I think you’d be a good minister.”

But the son would always politely decline. He was shy, quiet.

“I had no desire to do it,” Joel says now. “It was so far from me.”

Every year they would take at least one trip to India. They’d sit next to each other on that long flight and Joel’s father would always give him the same talk.

“You’d be great,” John would say. “You can help me.”

“Daddy,” Joel would say, “I’m not a preacher. You preach, and I’ll make you look good.”

One day, when John was 77, he was having dinner at Joel’s sister Lisa’s house. He decided to call Joel and give it another try. Dodie and Lisa told John he was wasting his time.

JONATHAN ZIZZO

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Joel says, closing his eyes. “It was a Monday.”

At first, it went the way it had so many times before.

“Hey, Joel,” the father said, “I was just wondering if you’d give me a break and minister for me.”

“Daddy,” Joel said like he always did, “I’d love to, but that’s just not me.”

This time, though, when they got off the phone, the son got a strange impulse.

“It wasn’t 90 seconds later I felt something down here,” Joel says looking back. He touches his chest. “It said, ‘Joel, you need to do it.’ ”

When he called back to tell his father that he’d do it, his mother and sister were stunned.

Joel now jokes that it was the most miserable week of his life. He figured he’d try it once, to make his father proud. He told Victoria not to talk to him until after the Sunday service.

That Friday, John was admitted to the hospital: a complication with his dialysis. Joel’s mother had been sick in the early ’80s, when doctors told her she had a tumor on her liver the size of an orange. But she prayed vigilantly and focused on living a normal life, and she made a miraculous recovery. Joel just assumed his father would get better soon, too. That Sunday, John listened to his son’s first sermon over the phone in the hospital. The nurses told Joel they’d never seen his father so proud. A few days later John had a heart attack and “went to go be with the Lord,” as Joel puts it.

The son was in a daze, but the same thing that told him he needed to get up and minister that first time now told him he needed to step up and pastor his father’s church. This was 1999, and the membership at Lakewood had grown to nearly 6,000 people. Joel’s goal at the time was to maintain what his parents had built.

“I did my best; I didn’t know what I was doing. Heck, I barely do now.”

At first, he tried to imitate his father’s style, which was a little stodgier, a little more traditional than how he preaches today. It didn’t feel right, though. So he made a conscious decision to sound more casual and accessible—more like himself.

“I wanted the guys I played basketball with at the YMCA, guys who didn’t go to church, to understand everything I was saying. I never wanted anyone to think I was talking over their heads.”

He spoke less about the figures in the Bible and focused more on stories about people overcoming hardships, stories about faith bringing people through terrible times. He’d write out his sermons and memorize them, sometimes recording his voice to study it. After so many years editing his father’s sermons for TV, he was able to self-edit and focus on the specific language he wanted to use. Osteen repeated words he thought were positive and cut things he thought might turn people off.

“A lot of people, life’s beating them down enough. They could come in here, and I could say, ‘You know what? You’re all sinners. You probably haven’t lived right today.’ But they already know that. They don’t need to go to church to feel guilty. You already feel guilty because you didn’t spend enough time with your kid. You haven’t broken that habit. You know what, God’s looking at the fact that you took the time to come out to church or to the stadium. He’s got something great for the future.”

It’s the same message Osteen preaches today, the same thing he writes about in his new book. His idea is: If you literally say the positive words out loud, you’re more likely to embody them. It’s about the power of belief. It’s a little like The Secret

Within years of the son taking over as pastor, membership at Lakewood grew exponentially. In 2005 the church moved into the former Compaq Center, making around $100 million in improvements and upgrades, including an additional five stories of administrative space. His relatively noncontroversial message and approach have a massive appeal—he’s a relaxing voice in a complicated, modern world.

But this positive outlook, sometimes called the “Prosperity Gospel,” can draw the ire of critics. Conservative blogger Matt Walsh wrote a post in 2014 calling Joel and Victoria Osteen “heretics.” Other preachers have questioned Osteen’s theological understanding. They say Osteen’s message could have people focusing on themselves instead of God or Jesus. Some evangelicals mock his happy attitude.

But Osteen says he almost never sees or hears the criticisms. He doesn’t read blogs or comment sections. “It’s funny,” he says. “It seems like I’m naive, but everybody I talk to, they’re saying, ‘You helped me, I like listening to you.’ And the stadiums full of people? They’re not coming because they’re critics. They’re coming because you touched their life.”

When he talks about prosperity, Osteen says he isn’t referring to just money. “Prosperity to me is having peace. It’s having good relationships. It’s being able to pay your bills, yes, but it’s being able to bless somebody else.”

He believes the idea that he doesn’t teach enough Bible lessons is wrong, too: “I won’t talk about it specifically—‘Hey you’re a sinner,’ but I’ll talk about lack of integrity, about compromise. I turn it around. It’s the same message. I’m just coming at it from a positive point of view. Ninety-nine percent of people will respond to that. And I think that’s why it’s crossed so far out into the world.”

***

The crowd starts building Saturday afternoon. At first it’s a trickle, then more, then more. The earliest are mostly die-hard Osteen fans who want to make sure they’re in the front row. But soon there are thousands of people streaming in. Traffic around the stadium stands still. Residents in nearby apartments come out into the streets to see what’s happening.

The ticketholders are a broad array of people. Most paid $25 to be here. There are all ages, all races. Some people are here in their finest attire, with jewelry and formal wear. Others are wearing windbreakers and scuffed tennis shoes. Children run up and down the aisles playing tag. Former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, long an Osteen fan, takes her seat near the stage, not far from Duck Dynasty’s Willie Robertson, who’s here in a fleece, skinny jeans, neon green high-tops and his trademark American flag bandana.

BOB ADLER

Soon there are more than 30,000 people in the stadium seats. A few thousand more are streaming the event live on YouTube. And more still are watching it on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. The Night of Hope hashtag is trending across the Bay Area.

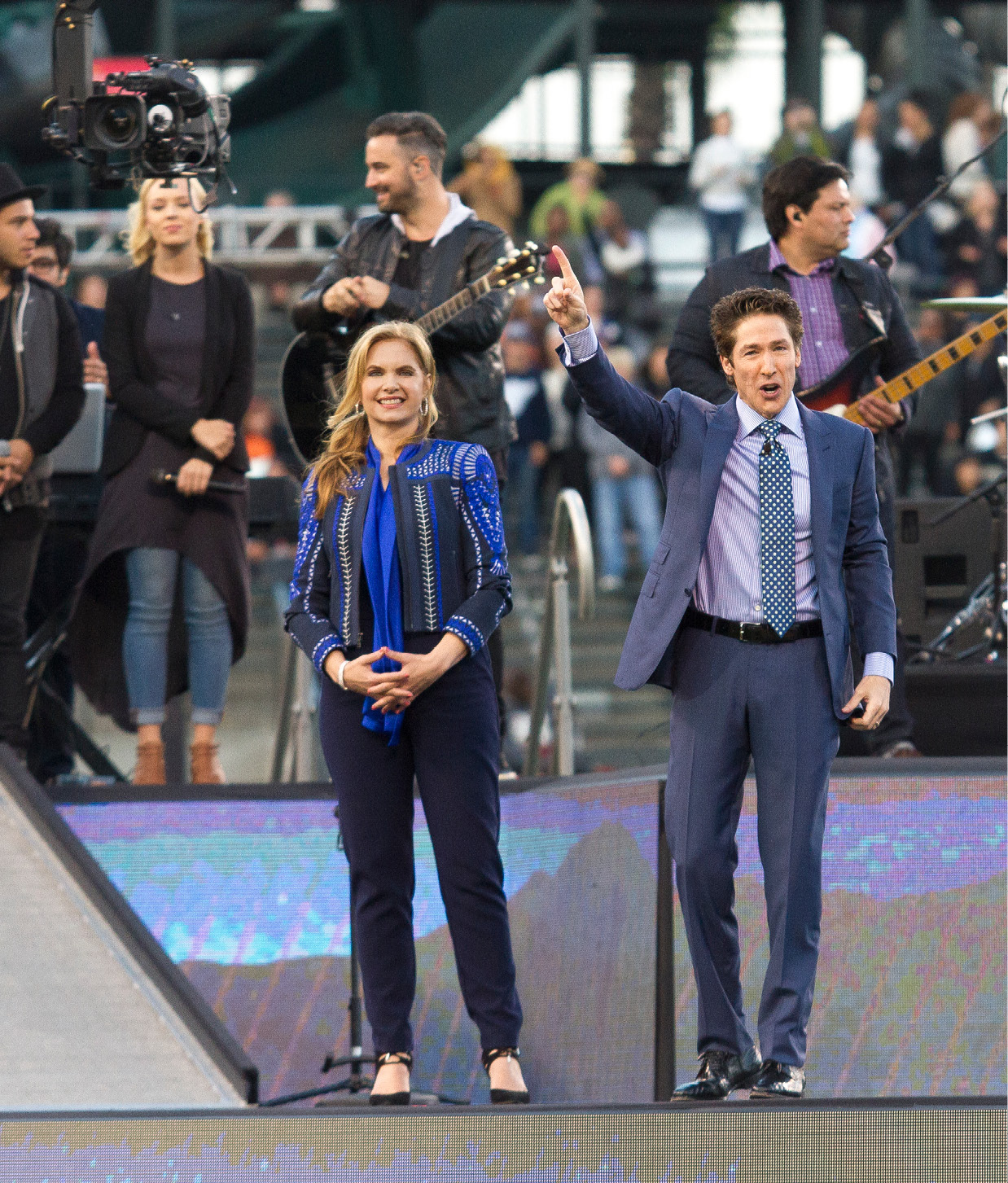

The sun is still up when the music begins to play—a mix of slow and fast praise hymns. Joel and Victoria walk onstage to thunderous applause. He’s wearing a blue suit, a dotted tie, and a sharp, pinstripe shirt. She’s wearing a blue Western-style top with a matching scarf. Together they look like smiling models from an ideal American suburb somewhere.

“God is smiling down on ya tonight,” Joel tells the crowd. “He doesn’t even need to look through the roof; he can look right down on you. God is for you. The most powerful force in the universe is on your side tonight! All you have to say is, ‘God, I want to receive what you have for me tonight.’ ” He adds: “This is going to be your best year so far!”

“God is going to help you with whatever you’re facing,” Victoria says. “You already have everything you need inside you.”

She tells a story about a time she made chocolate milk but got a phone call before she could drink the whole thing. She explains that when she came back, 30 minutes later, all the chocolate had settled to the bottom of the glass. “Sometimes those good things settle to the bottom, and we don’t believe we can do what God called us to do. You need to take a God-spoon and stir up your faith with everything that’s in you.” Victoria repeats “chocolate milk” over and over—positive words.

“Prosperity to me is having peace. It’s having good relationships. It’s being able to pay your bills, yes, but it’s being able to bless somebody else.”

There’s more music. More stories. Joel talks about the strength God gives people during hard times. Victoria talks about how “God chose you” the way adopting parents pick out an infant at a hospital. Dodie comes onstage to tell the story of her recovery from cancer. Ten pastors from local churches—a mix of conservative and liberal—are invited up to give positive declarations and prayers, one at a time.

At some point, the music quiets and Joel takes the stage alone to talk about when his father died and how he had to take over the church. When he mentions his father’s last days, how proud John was in the hospital, Joel’s voice begins to crack. He has to stop for a moment and wipe his eyes. The moment doesn’t feel contrived. In fact, he seems a little annoyed at himself.

“I’m the biggest crybaby. I can’t help it, though.”

The crowd erupts in the biggest cheers of the night.

He goes on: “God wants to do more than you can ask, think or imagine. God’s dream for your life is so much bigger than your own. I never dreamed that I’d be doing this today. I was content working behind the scenes. But God had something else planned for me. You have gifts and talents in you right now that you haven’t tapped into. It might not be like me, up here in front of people. You might be teaching at that school; one day you’re gonna be running that school. You may be working at that business; one day you’re gonna be owning that business.”

His voice builds. The man who was quiet and demure a day ago now seems like he’s powering an entire stadium. The temperature has dropped, but these people feel warmth.

“Get ready,” he says. “Get ready for some new things God wants to do with your life!”