“Dad had a heart attack about an hour and a half ago. They believe that he has a fully blocked artery.”

That’s how my 28-year-old brother broke the news. It was 12:53 a.m. on Friday, Feb. 3, 2017, when my phone lit up from the kitchen counter—where it was spending the night, a precautionary measure against the disturbance of my sleep patterns.

At 6 a.m., I stare blankly at the green bubble of text, but my groggy brain can’t comprehend the words. Then panic sets in. And anger. A text? Really, Michael? I silently curse at my brother for his communication method as I stumble toward the closet and pull out my luggage.

Three years prior, my dad suffered his first heart attack. I didn’t understand at the time what the “Widow Maker” artery was, but a stent and an extreme diet makeover soon followed, along with an assurance that, with lifestyle changes, he’d be just fine. But months passed and dedication waned. A few stress cigarettes and salty rib-eyes slid back into his routine.

Now this one, heart attack No. 2, requires six tanks of gas, seven days and nearly 600 messages to organize the chaos of extended family, hospital transfers, surgery schedules, diet plans and nicotine patches. On the eight-hour drive home to Kansas City, Missouri, I wonder how anyone got anything done before you could just mass-text “ICU 237-C” to 35 aunts, uncles, cousins and that one neighbor who is more curious than caring.

I’m wondering because, when I got that sobering late-night text, I was on my third day sans “instant communication.” This monthlong challenge was conceived in an attempt to find out if what they say about our phones is right—do they rob us of higher levels of connection with our friends and families? Do we prioritize the second screen over the beautiful, giant world right before our eyes? Does social media sharing rob us of the satisfaction for the sake of ourselves?

I wouldn’t call it an addiction, but I know that I check my phone when I first wake up, when I’m waiting for a meeting to start, when the meeting has a lull, during meals (with or without company) and at most red lights. And if I’m being honest, I checked it again just now after writing that sentence.

So for 672 excruciating hours—28 days—I eliminate the near-constant digital conversations, with one goal in mind: to see whether the expensive, brain-rotting rectangle in my pocket has robbed me of something bigger.

I expected a gentle (annoying) reminder of moderation and balance with a sharp dose of nostalgic pre-smartphone bliss. Instead, I spent a month trying to prove that I’m capable of connecting on a deeper level than “Ur my bff. Love u see u soon.” As if the ability to leverage current technology and be a caring human being are mutually exclusive. Sure, I’m on Snapchat too much. Does that mean I’ve forgotten the importance of a phone call or visit on a friend’s birthday or when they’re struggling?

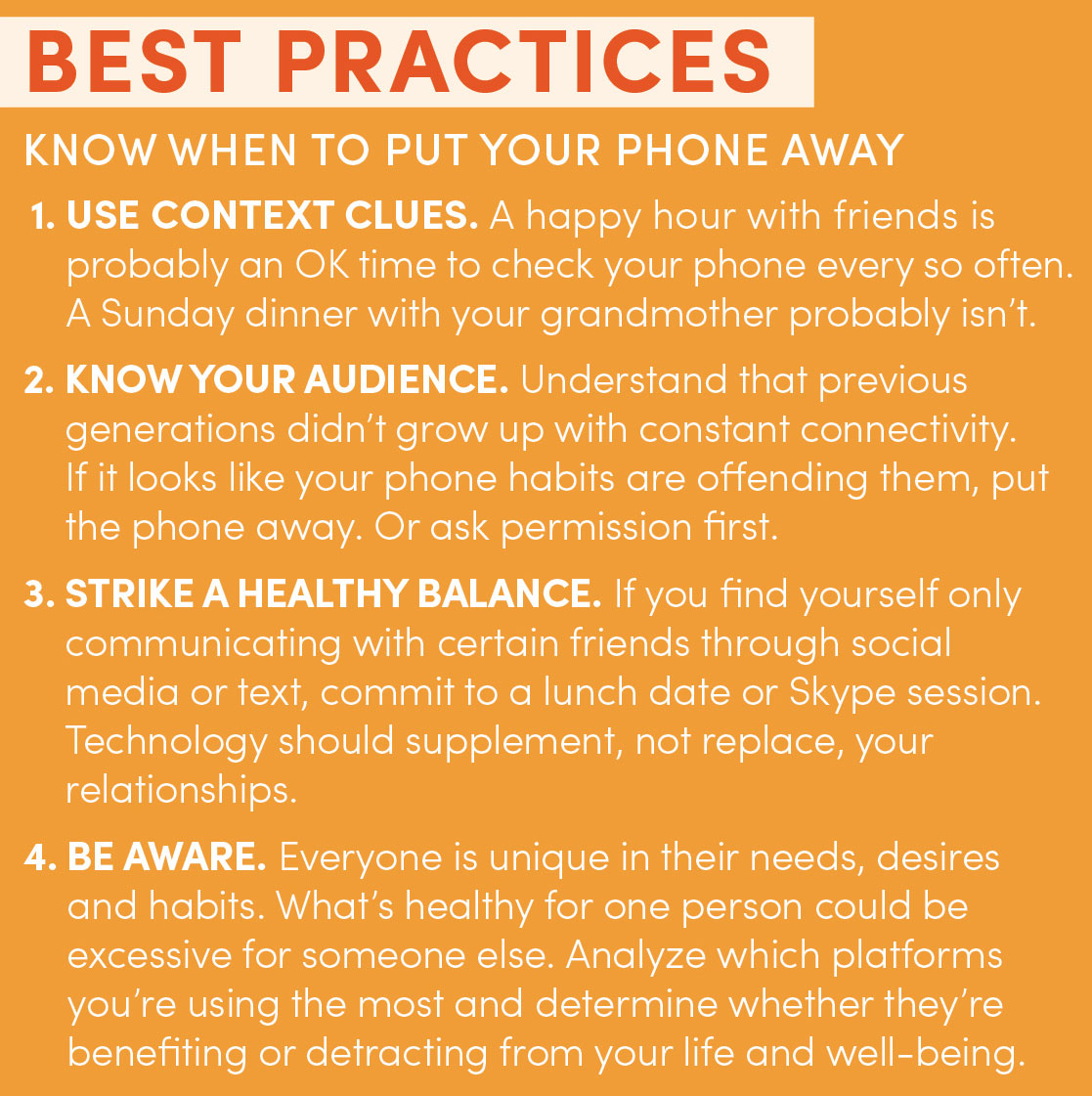

Maybe the problem isn’t solved with generalizations; maybe it’s a need to be more aware of what kind and how much of a role technology plays in our lives and relationships.

What’s the deal with these kids, anyway?

I’m 26. I’m entitled, narcissistic, self-absorbed, authority-averse and not likely to work under you for very long, because you don’t offer free snacks, and I don’t feel this entry-level position allows me to change the world. These are descriptions so often bestowed upon members of the “Me Generation”—those roughly 18 to 35 years old. I don’t know if all of that is true, but the one stereotype that definitely fits is that I am technology-obsessed. I won’t leave a voicemail—I’ll just text what I was going to say. I won’t write letters to my great aunt—I’ll send her a Facebook chat. I won’t get up and walk 10 steps to your desk—I’ll G-chat you.

Related: Simon Sinek: The Secret to Leadership and Millennials Is Simply Purpose

Jean M. Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of Generation Me and The Narcissism Epidemic (both based on surveys of more than 11 million people), is an outspoken source on the rise of narcissism in today’s youth, especially millennials. She argues the problem lies within America’s culture of self-esteem, in which children are raised to believe their feelings of self-worth are valid, regardless of actual accomplishments.

In a November 2015 piece for The Atlantic, Twenge wrote: “The prevalence of digital technology and the greater freedom of individualism both encourage more information-seeking, novelty, and risk-taking, but provided fewer opportunities for emotionally close, long-term relationships.”

Author, social scientist and management speaker Joseph Grenny coined the term “EDI,” or electronic displays of insensitivity, which is when we cause a rift in our friendship by pulling out our phones at a time that could be offensive to others.

Related: How to Speak Well… and Listen Better

So has the prevalence of digital communication stunted our social skills? Does our increasing narcissism stop us from caring about meaningful relationships—pushing instead for likes, comments and retweets?

That phone will rot your brain!

My parents first said it about TV, then video games, then the internet, and now the phone. To understand the brain-rotting argument, Melissa Dickson says we need to look back to history. A research assistant at St. Anne’s College at the University of Oxford, Dickson is part of a research team studying how Victorian-era society responded to technological advances and what parallels are present with current responses.

In one example she cites, the parallel is striking. A 1906 cartoon published in a satirical British weekly magazine depicts a man and a woman sitting side by side, using a telegraph to flirt with each other. “Different technology, same joke, underpinned, I think, by the same anxiety that real human interaction, mediated by nothing bar visceral experience, is under threat from the technological innovations that we have assimilated into our daily lives,” Dickson says.

Of course, the telegraph didn’t bring about the end of the awkward social situations we call flirting. Neither did the telephone, the fax machine or the advent of the internet. Brian Primack, Ph.D., director of the Center on Research on Media, Technology, and Health, at the University of Pittsburgh says tossing casual blame at innovation allows us to ignore larger, contextual information.

Take the printing press, for example, which was thought by many at the time of its invention to be the end of culture. It wasn’t, of course, but even centuries later it did allow Nazi propaganda to be printed and distributed with a look and feel of authenticity. The problem, Primack says, is that we blamed technology, rather than teaching people the necessary critical thinking skills to differentiate propaganda from real information. Or fake news from real news. A timeless lesson.

Smartphones are different, though. Never before have we had continuous access to ceaseless distractions. According to a 2016 study by Deloitte, Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 check their phones 82 times per day. I tried to keep track one day and lost count at 32—sometime around lunch.

“A lot of people don’t really think about it consciously enough to say, ‘Wow, this is taking a lot of time, a lot of energy, a lot of me,” Primack says. “And it’s not necessarily giving back to me.’”

I wonder what I’m missing when I’m looking down. What meaningful connections do I let slide between the space of my digital world and the real world? Nicholas Epley, the John T. Keller Professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago and author of Mindwise: How We Understand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want, says what’s lost is something fundamental to human connection—something we don’t even realize happens during a conversation.

“Spoken voice communicates something fundamental,” he says. “It communicates the presence of your mind. Your voice contains paralinguistic cues, the emotional experience while you’re having it.”

Related: 10 Ways to Be a Better Communicator

But, Epley says, that doesn’t automatically mean we’ve lost our ability to communicate altogether. “Someone in a sedentary job doesn’t lose the ability to walk,” he offers as an extreme example.

Stay woke.

“Don’t spend too much time on your phone” feels vanilla, like “Make your bed” or “Take a walk outside.” Am I really losing something important because my pillows aren’t arranged? (Sorry, Mom.)

A growing body of research points to increased risk factors of depression, anxiety, loneliness, jealousy and sleep deprivation when spending large chunks of time on social media. But a 2016 study led by Primack found that the number of different platforms used—Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, Tinder, whatever—was a much bigger risk factor than the total amount of time spent.

And that makes sense, he says. “Each of these little worlds has its own rules, its own idiosyncrasies. If you’re trying to navigate eight different ones, that’s potentially a problem.”

Related: Why Social Media Is Ruining Your Self-Esteem—and How to Stop It

Social media and millennial communication is simply the technology of today. And like every other era of humanity, technology should supplement, not replace, our face-to-face relationships. Shooting a quick text to let a friend know I’m thinking about her doesn’t replace the two-hour catch-up call we’ll have later this month when life slows down. But sending daily Snap updates—my cat stuck in the blinds, my #Healthy kale salad, an “is it 5 p.m.?” sad selfie—can never replace laughing for 30 minutes when I pronounced meringue as merr-en-goo. That’s a memory texting could never replace.

So no, I don’t think checking my phone during a lull in a meeting means I don’t respect those in the room. I don’t think texting my dad “How is cardiac therapy going?” means I wouldn’t jump in the car and drive eight hours if I sensed that he was having trouble.

Leveraging technology, for me, was learning when it was enhancing rather than detracting from my relationships. Sending “Dad is being transferred to KU Med-West for a second opinion” to 30 people is efficient. Checking my newsfeed 14 times before lunch without realizing is troubling. Ty Tashiro, Ph.D., author of Awkward: The Science of Why We’re Socially Awkward and Why That’s Awesome, says a challenge like this can help refocus you on the small but important parts of life.

“I always like that experiment where you remove something in a very stark way,” he says. “I think those help you see the usefulness of something versus the slow slide into some habits that are unhelpful.”

That’s what happened. I learned to appreciate the role of brief, modern communication. I began to look at these platforms and tools in a different way. Rather than checking my Snapchat stories every day just because they’re there and available, I began to ask myself what that brings me. Joy? Connection? Happiness? Jealousy? Loneliness? Instead of telling myself to restrict time on Snapchat, I analyze how my life could benefit, or be harmed, by these mindless habits.

As David Foster Wallace famously said in a 2005 commencement address: “That is real freedom. That is being educated and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.”

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a text to send. #Merr-en-goo.

This article originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.

Cecilia Meis is the editorial director for SUCCESS and a digital nomad. She writes about other digital nomads, solopreneurs and the future of work.

- Cecilia Meishttps://www.success.com/author/cecilia-meis/April 10, 2023

- Cecilia Meishttps://www.success.com/author/cecilia-meis/April 1, 2023

- Cecilia Meishttps://www.success.com/author/cecilia-meis/March 13, 2023

- Cecilia Meishttps://www.success.com/author/cecilia-meis/March 1, 2023

- Cecilia Meishttps://www.success.com/author/cecilia-meis/February 24, 2023