Have you ever felt deflated after achieving a huge goal? You climbed Mount Everest, sold the business you started, or won acclaim in your field, as boxing champion George Foreman and moonwalker Buzz Aldrin did in theirs. Once the initial buzz is over, you’re a little down in the dumps and wonder what’s next.

First, realize this: It’s natural to feel this way. After all, you sank tremendous resources into your goal and probably put other parts of your life on hold, says Maria Newton, a motivation researcher and interim associate chair of the University of Utah’s Department of Exercise and Sports Science. Plus you might be disappointed that when you finally crossed that marathon finish line (or business equivalent), the applause wasn’t as thunderous as you had hoped.

Related: Rohn: 4 Tips for Setting Powerful Goals

“You’ve sacrificed a lot. You’ve achieved a large goal, and I think it’s really useful to understand that there will be a letdown. The letdown may be because you’re a tad relieved that you were able to achieve it,” Newton says. “It’s totally expected.”

The message underlying your emotions is that it’s time to take care of yourself. You need to recover psychologically and physically, Newton says. Resting will boost your emotional outlook while providing the time and space to answer the question, what’s next?

Here are more tactics to help you cope…

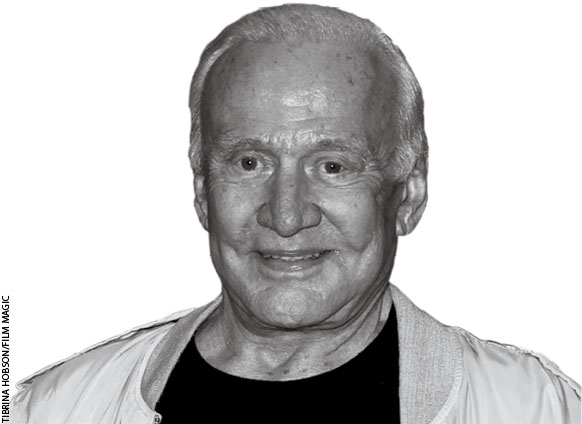

Buzz Aldrin

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, the second human—after mission commander Neil Armstrong—to ever set foot on an alien heavenly body. That fact follows him wherever he goes. It’s what strangers ask him about, this feat accomplished by a 39-year-old who earlier had graduated third in his class at West Point Military Academy and was decorated for shooting down two enemy MiG fighter jets as a pilot during the Korean War.

He admits that he suffered from depression and alcoholism in 1972 after his NASA career and subsequent short stint in the Air Force. He wanted to keep planning space activities, but NASA veered in a different direction. The former astronaut found himself at loose ends.

Related: Is Success Making You Depressed?

Aldrin realized his depression probably was an inherited trait because his mother died by suicide a year before his moonwalk; his grandfather also died by his own hand. He recognized he had become “disillusioned, disappointed when things weren’t going my way, and I would just withdraw from the outside world. I didn’t like Mondays at all, and I began to drink a bit. I was pretty good at doing that as a normal fighter pilot, but now it began to get out of hand. Clearly I began to realize I was in trouble.”

He realized he had to cure the drinking first, which was reasonably under control by 1979, and then he could work on the underlying causes of why he was discouraged and depressed. “Hell’s bells. You went to the moon; you were on the first landing,” he says aloud, as if to answer the question, “What do you expect?”

Over time, Aldrin realized he had to do things for which he had special talents. So drawing on his expertise and his Massachusetts Institute of Technology doctorate in aeronautics and astronautics, he developed a system for travel to Mars called the Aldrin Mars Cycler and obtained a few patents, such as one for a permanent space station. Nowadays, Aldrin, 86, is pushing for a plan to colonize Mars—he hopes it happens by 2039, the 70th anniversary of his moon landing—via his research and advisory work at the new Buzz Aldrin Space Institute at the Florida Institute of Technology.

His advice for others facing the post-accomplishment blues: Keep your options open. Look around and test different opportunities that can be satisfying and that can use your talents and give you the satisfaction of achievement.

Related: 10 Steps to Achieve Any Goal

“You may be at the bottom of the pit,” Aldrin says. “You’ve got to move out of that pit step by step… with a willingness to have things happen slowly. They’re not all going to happen just as you want right at first, but a person needs a determination, a sense of camaraderie with other people. Learn from others, share freely and begin to move up the ladder in a different direction. I don’t think you can go back and just repeat the same thing over again. In my case, of course, there was no option to become an astronaut again.… Those days were over.”

Diana Kander

Serial entrepreneur Diana Kander’s typical pattern: She launches a startup, grows the business to make it repeatable and scalable, and when she has learned all she can from the business, “that’s when my interest starts to decrease because I love learning so much.”

She tries to make her next move inside the same organization, asking herself, What else can I do here to create new value for customers? “If that’s not an option, I’ll try to find that spark somewhere else,” says the innovation coach and ex-lawyer who teaches entrepreneurship at the University of Missouri.

And so it went with the legal consulting company she started by herself, KR Legal Management in Kansas City. Kander built it up so that by year four, “it was a machine.” She was just another person running the firm as opposed to solving difficult startup-type problems, so she sold KR to an employee.

Her advice for others: Even if you have an all-consuming career, take time to plant seeds for what you’ll do next and try as many things as possible. If you think you might want to go into a particular type of business, try to meet people in that space to understand what it would entail. You might assume you want to own a restaurant, but you might change your mind after talking with people in the industry. Don’t quit your job and then start looking for an opportunity; you’ll feel pressured and scared.

Kander says she personally doesn’t remember that sagging feeling after meeting a big goal because she stays busy with more than one thing at a time. For instance, a month after she sold her last company, her new book All In Startup hit the New York Times best-seller list, and a month and half later, she gave birth to her son. “It works for me,” she says of the busy strategy, “but I wouldn’t say it’s a recipe for everyone.”

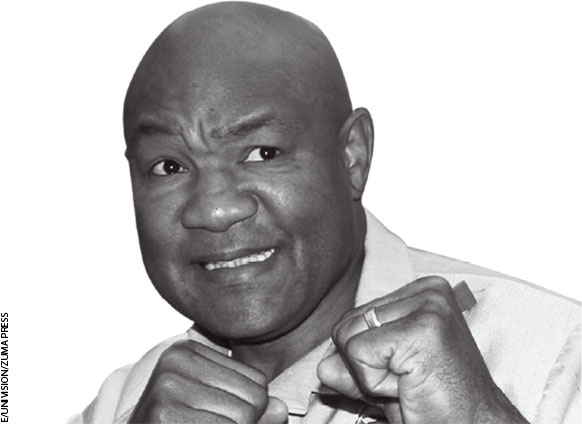

George Foreman

Two-time world heavyweight champion George Foreman is a Boxing Hall of Fame member who won an Olympic gold medal in his 25th amateur fight and racked up 68 career knockouts. Today he’s best-known by the younger set as an amiable TV pitchman. His George Foreman Grill reportedly earned him a $137 million lifetime deal, and he recently launched a venture selling artisanal meats for the grill at his online George Foreman’s Butcher Shop. Ebony calls him the master of reinvention.

In 1977 Foreman faced that what’s-next question after losing a bout to Jimmy Young by knockout. Unconscious and with his life on the line, Foreman had a religious experience informing him that it wasn’t his time to die, he says. Profoundly moved, he quit boxing to become a minister and today remains pastor of Houston’s Church of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Speaking from his Houston-area estate, Foreman alludes to the long layoff before returning to boxing: “Ten years, I didn’t even make a fist.” Then, according to the International Boxing Hall of Fame, he “embarked on one of the most improbable, yet successful, comebacks in sports history.”

“It was a hard thing because I had this freedom to be a human being,” says Foreman, recalling his near-decade of relished anonymity. “I didn’t want to cut into that.”

But even stronger was his need to put some money in the bank— “I was broke,” he admits. Foreman came out of retirement in 1987 to earn the money to support his family as well as keep open his namesake youth center in Houston.

To do so, he battled the naysayers. “Nobody wanted to promote me, so I had to sell myself, especially on television, to prove that I was still good. I’m almost 40 years old,” he recalls. “People said, ‘He’s too old’ and ‘You’re going to get hurt.’ I had to sell myself, so I learned to sell.” Madison Avenue took a liking to Foreman as he won, so he landed commercials for McDonald’s, Nike, Doritos and others.

Related: How to Deal with Critics and Rejection

He was so good at promotion that he was approached with the idea of putting his name on an electric grill manufactured by Salton. After all, he made money pitching for other companies, so why not pitch his own product? Foreman dismissed it as a toy until his wife, Mary Joan, tried the grill, liked it and used it to cook a burger he enjoyed. He signed on.

He soon made history by becoming the oldest-ever world heavyweight boxing champ at age 45. At 48, he decided to quit boxing on the same day he lost a fight to Shannon Briggs and was handed his first $1 million check for the grill.

If given a do-over, Foreman, now 67, says he’d remain super-ambitious but wouldn’t be so singularly focused as a young boxer. He regrets that when he flew to Jamaica in 1973 to fight Joe Frazier, “I didn’t even know the color of the water was blue because I was so focused on that boxing match. I didn’t eat the local food. If you ask me about Jamaica, I knew nothing.”

Given a second chance, “I would’ve made certain that every day was lived out, not just huffing and puffing and sweating and eating my protein and all that. I would’ve lived every day.”

His tactic for avoiding letdowns is to move quickly from one goal to the next. Life has to be more important than an individual goal. If you emphasize one goal and lose, “you’re going to crumble.” Achieving something is not achieving everything.

As an older, wiser boxer and the father of 10, Foreman knew that he had to get home to preach on the Sunday morning after he won his second world championship and that he had to go to daughter Natalie’s school for open house a day or two later. Life wasn’t only about boxing. “It’s important that you keep busy. I tell my kids: Every time you hit that floor in the morning, you better hit it with, ‘On your mark, get set,’ like a track runner. Every time you hit the floor, you gotta have something that you’re working on. Otherwise you’re just going to melt away and be nothing.”

David Epstein

David Epstein of South Florida spent two decades building his global business-process outsourcing company, Precision Response Corp., before he sold it to media mogul Barry Diller’s USA Networks in 2000 for about $750 million. Eventually Epstein left the merged company and wondered, What do I do now?

He took the advice of billionaire businessman Wayne Huizenga: Take six months off. “Good advice,” says Epstein, who was then part-owner of the Florida Panthers hockey team (purchased from Huizenga in 2001). “I gave myself a good six months.” Then he tried different ventures, some as an investor and others as a board member or adviser.

“None of them really struck the passion,” Epstein recalls. “I kept looking for that. I was too young to retire, and I didn’t like golf enough to play every day.” Hockey wasn’t filling the void: “It didn’t keep me up at night anxious to get to work.” He soon co-founded Pet Style and PetStyle.com, an online community for pet lovers and thought he’d apply the same business principles used at Precision Response. “We put a lot of money into it, but it was largely unsuccessful.”

It was “a pretty big letdown” to realize that replicating past business principles didn’t translate to success, he says.

But everything clicked again in 2010, when Epstein returned to the customer-care business by starting C3/CustomerContactChannels in Plantation, Fla., with some of his former Precision Response executives.

His advice for others? Take your time figuring out what fires you up. “You can’t force it. Look for the spark.”

Tama Kieves

“I was on a beach just crying my eyes out,” Tama Kieves says of the moment she knew she’d had enough as an “overworked and soul-starved” Harvard Law School graduate toiling at a Denver law firm. She had gone into the legal field to play it safe, but while eating a dollar bagel at the beach, she felt “the happiest and most peaceful I had been in forever. Maybe success wasn’t about making a bazillion dollars.”

Related: I Quit My High-Paying Job, Lived Out of a Backpack for 6 Months, and Now I Couldn’t Be Happier

She quit her job. But what next?

Kieves had the vague idea that she wanted to write but had no idea what that meant. How do you make a living? Write what? Fiction? Nonfiction? “It was very unsettling,” Kieves says. “The only thing I knew was there had to be something else.”

She took a timeout, sleeping and grieving over her lost career and trying to return to an innocent mindset to open herself to something new. “I needed to crash,” says Kieves, who ultimately would become a success coach and best-selling author of This Time I Dance! Creating the Work You Love , the first of her books. But initially she took a job that paid the bills while she spent time figuring out what was next, what moved her, who she really was, and what she really wanted.

“Sometimes you have to serve onion rings to serve your vision,” Kieves says. “To me, it was this wonderful time of just getting off the grid, off the rails, in a deliberate way.” She came to realize that she wanted to write a book and help others find their callings. She started support groups to coach others. People told her: You should teach; you should speak. Kieves started offering individual coaching and workshops during her 12-year transition from lawyer to author. “I always tell people it took 11 years to believe in the dream and one year to write a book.”

Her advice to people who are stuck? Follow your real desire. It’s what holds the power. Don’t be beholden to fear. “If you choose your real desire, you’ll start moving forward,” she says. “Real success is doing the thing you know you’re on this earth to do.”

Related: When You Aim High, You Set Yourself Up to Fall Far—Here’s Why It’s Worth It

BEST PRACTICES

Regroup the Right Way

If you’re preparing yourself for the follow-up to a major achievement, try:

• Focusing on the journey.

Challenge yourself every day and notice how you’re improving daily. That way, you’ll appreciate the mini-accomplishments along the way to reaching a big goal, says Maria Newton, a University of Utah motivation researcher. If you’re totally focused on the goal, typically it doesn’t live up to expectations.

• Taking a little break after reaching a big goal.

Newton says this will allow you to heal physically, emotionally, psychologically and intellectually. Allow yourself time and space to look out over the horizon, and choose something else to work on.

This article appears in the February 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine.