Knock, knock.

I gently tap on the bedroom door and peer in. I hear my husband David’s rhythmic breathing. “Are you awake?” I whisper. Nothing. I ask again, this time a little bit louder.

“What’s up, babe?” He asks, his voice dripping with sleep.

My cheeks are stained with salty, almost-dry tears. My eyes begin to well up again. “Dr. Schneider died,” I say.

“Oh babe, I’m so sorry,” he says. “Come here. What happened?”

I crawl into bed and tell my husband that a former member of my therapy group emailed me with news that my therapist of several years had passed. I hadn’t seen him in months because I moved to a new city. He was 83, but in great health, so the news shocked me.

If you told me three years earlier that I’d be crying over the death of my therapist, I wouldn’t have believed you. Me? Crying over the death of someone I paid to treat me? Someone I had a purely clinical relationship with?

But this is where I found myself just last year.

* * *

This isn’t the first time I’ve written in SUCCESS about being plagued by the physical, emotional and mental symptoms of anxiety. Rapid breathing, trouble sleeping, dizziness? Check. Catastrophic thinking, fear that everyone hates me, worry that I’m an impostor? Check, check, check.

I was never in denial about being an anxious person—I always accepted this fact. I just never thought I needed clinical help. I thought I managed my anxiety quite well. I got by.

But then around three years ago, while living in Dallas, my anxiety came to a head. There wasn’t one contributing factor, but rather many: I was planning our wedding, my husband would be matching for his medical residency soon—which could bring us to a new city—and I’d just started a new job. Every day I struggled to take deep breaths and my shoulders were so tense you’d think I’d lifted weights for 10 hours, both of which are hallmark signs I’m in panic mode.

In the past, these symptoms would eventually abate. This time, they didn’t.

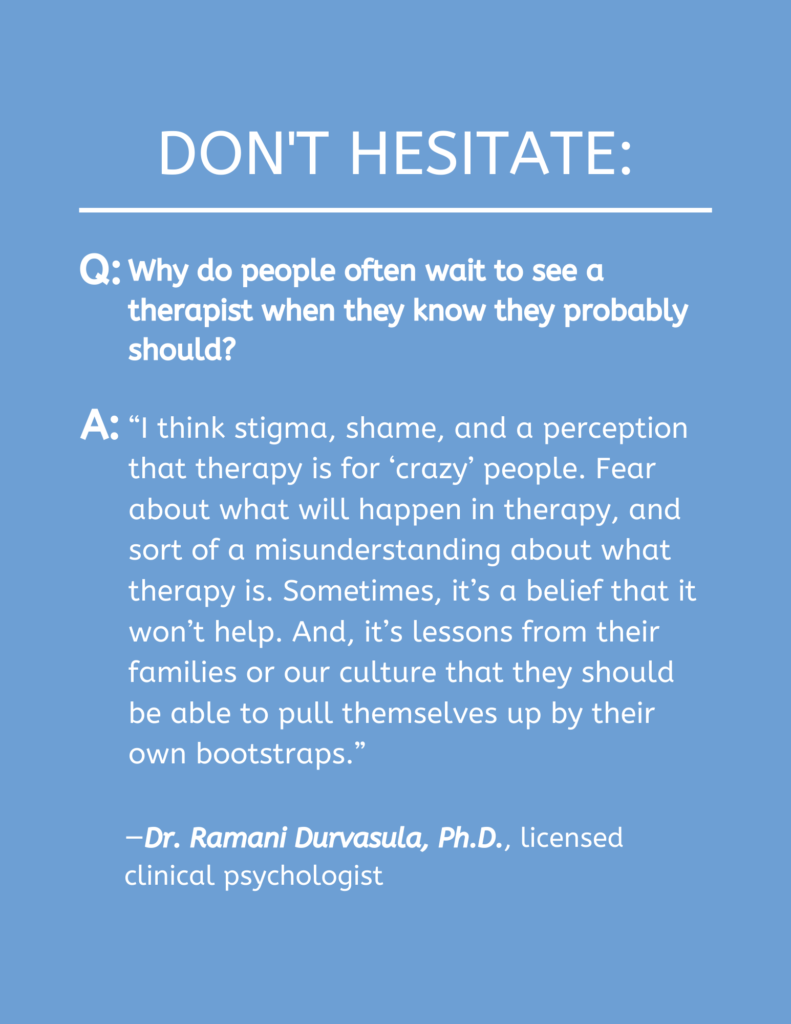

Dr. Ramani Durvasula, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at California State University, Los Angeles, and a licensed clinical psychologist, says people often struggle to identify when they should see a therapist for the first time. She advises people to look for three things: 1. Interference in your life, such as your job, work and relationships; 2. Your perceived level of distress or discomfort; and 3. Other people noticing you don’t seem like yourself.

“I think a lot of people say, ‘Oh, it’ll pass’ or, ‘I need to toughen up and figure this out myself,’” Durvasula says. “But if any of those three things that I just listed are happening, it’s probably time to consider consulting a therapist.”

I had the first two, and then the third came along swiftly. I told my husband I’d been flirting with the idea of therapy, and he thought it was a great idea. He was in medical school and had just shadowed a psychiatrist he loved: Dr. Schneider. I gave him a call.

The day I walked into my first therapy appointment, my anxiety was a 9 out of 10. I hesitantly entered the waiting room and nervously tapped my toes, looking at all of the dated furnishings and décor around me. Dr. Schneider came out, and his warm smile, slow gait and gentle aura put me at ease. He looked like a grandpa, balding with thick glasses. Heart racing and sweat pouring from my armpits, I detailed some of the problems I’d been dealing with before giving him a brief history of my life thus far.

At the end of our session, he told me he treated medical students and their significant others at a heavily discounted rate—it was his way of giving back.

I left his office feeling lighter. I was optimistic that I’d finally get a grip on this “thing” I’d been battling my entire life. I recently looked back at one of my old journals, and found this entry dated December 28, 2016, a few weeks after I began going to therapy:

“David recently encouraged me to start seeing a therapist, Dr. Schneider, for my anxiety. I think for a long time, I ignored or denied that I had generalized anxiety disorder, but I very much do and it’s very real and present all of the time. It’s exhausting to live like this. I had a moment of clarity recently that the way I drive myself crazy with my worried thoughts isn’t normal. Dr. Schneider was cool—he’s this like 80-year-old Jewish guy. I enjoy talking to him. I hope he can help me figure some things out.”

For about two years I saw Dr. Schneider weekly. He confirmed that I have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), as well as some obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (which differs from obsessive compulsive disorder, or OCD) tendencies. He helped me unpack certain things in my past that contributed to these problems, like my childhood. He gave me advice for how to make small changes in my life that would lead to big improvements. But more than anything, he listened.

Dr. Schneider also helped me see how much anxiety impacted my life. It wasn’t just that I had a mind on overdrive. Anxiety caused my sleeping problems, my dizzy spells, and my loss of appetite when I’m overwhelmed.

My anxiety began to very slowly ease up. There were days when I wasn’t wound up tight like a rubber-band ball every waking minute. I got more restful sleep. I could catch my breath.

Eventually, Dr. Schneider suggested I join a group therapy because of my pathological struggle to speak up. I’ve always found it extremely difficult to assert myself and freely speak my mind. Being in group therapy helped me experiment with bold, confrontational behavior with a safety net. Anything I said was fair game, and everyone in the group was there to support me.

After around two years of therapy, my husband and I moved to Chicago. Dr. Schneider said that although I was welcome to call him at any time, he felt like I was in a great place emotionally. I teared up after walking out of his office for the last time, simultaneously sad that I might not ever see him again and proud of all I’d accomplished with his help.

* * *

Six months after we moved to Chicago, things took a turn. Although I’d had some challenging life events since we’d moved, including the death of my beloved grandmother and a shoulder surgery that left me impaired for months, I was doing OK. I had a great support system and good coping mechanisms in place.

And then my mom told my dad she’d met someone else and wanted a divorce. I thought I was coping OK, but I wasn’t. Although my “hallmark” anxiety symptoms weren’t present—things like rapid breathing and tense shoulders—my anxiety manifested in different ways. I had trouble focusing on my work and I was forgetting things. I slept a lot and my acid reflux had worsened.

Allison Johnsen, LCPC, BCC, manager of behavioral health at Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital, says anxiety and depression can present in different ways for different people, especially following a traumatic event. Some people might feel tightness in their chest, while others might have gastrointestinal issues.

“You know based on how you usually are whether something is different,” she says. “Sometimes the body will tell you, sometimes the emotions will tell you first. It just depends on the person.”

I learned of Dr. Schneider’s death a few months before my parents’ divorce, so I found a new therapist in Chicago named Ingrid. She couldn’t be more different from Dr. Schneider. She’s young—around my age—and although she’s supportive and has helped me a great deal, she isn’t as frank and direct as Dr. Schneider was. It’s a different type of therapeutic relationship, but I’ve learned that’s OK.

“Therapy is a very unique health care relationship,” Durvasula says. “Different people have different needs. Some therapists are much more in your face. Some therapists are much more warm and fuzzy. Just like we have different preferences on the people we spend time with, we may very well have that with our therapist.”

After we moved to Chicago, I found myself missing Dr. Schneider, or as I often called him toward the end, Jerry. I looked forward to our weekly sessions. This therapy was the definition of personal development for me. It didn’t come out of a best-selling book, and there was no paint-by-numbers process. The work was hard, but it helped me make significant improvements in my life.

Faced with an anxiety-inducing situation, I’d often ask myself, What would Dr. Schneider say? Nearly every time, I guided my action based on the advice I envisioned he’d give me.

We bonded in a unique way. At times, he’d ask my opinion on things as a woman nearly 50 years his junior, like the Harvey Weinstein scandal. He joked about how he was the ring bearer in his grandson’s wedding. He marveled at the ubiquity of social media. Why in the world would someone want to share photos of their trip to Italy with 500 people? He once asked me.

If you’ve never been in therapy, this might sound strange, but I grew to miss him like a close friend when he died. Not only did he know my entire life story, but he helped me improve my mental health in a significant way. I am a more confident person because of him. I’ve always strived to live a life that is both fulfilling and meaningful, and because of him and the work he helped me put into myself, I’ve moved closer to that vision.

The group member who notified me of Dr. Schneider’s passing, Steve, attended the funeral. Dr. Schneider’s large family was there. He had often opened up about himself in individual and group sessions, speaking fondly about his career, as well as how important all of his relationships were to him. He was married for 59 years and had four children and 11 grandchildren. His first great-grandchild was born just before he passed.

Steve told me of a poignant moment I’ll never forget. Dr. Schneider’s grandson spoke, and said he’d been at his grandfather’s bedside in his final days. “Are you afraid to die?” His grandson asked him.

“No,” he said. “I’m afraid to not live.”

Related: How to Improve Your Mental Health: 9 Keys to Your Well-Being

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of SUCCESS magazine.

Photo by Mary Long/ Shutterstock.com