When J.B. Mauney smiles, which is often, dimples carve crevices in his cheeks.

Those dimples are present now, as Mauney tries to contain a secret. It’s the penultimate night of the 2016 Professional Bull Riders’ season, and Mauney, one of the top bull riders in the world, is in contention to win his third world championship, which would tie him for the most ever. He is third in points with one event left in the season. He has two routes to a championship in the finale tomorrow at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas: He could pick an easy bull, score moderate points and hope the guys in front of him blow it. Or he could pick the rankest bull there is, score big and storm past the competition.

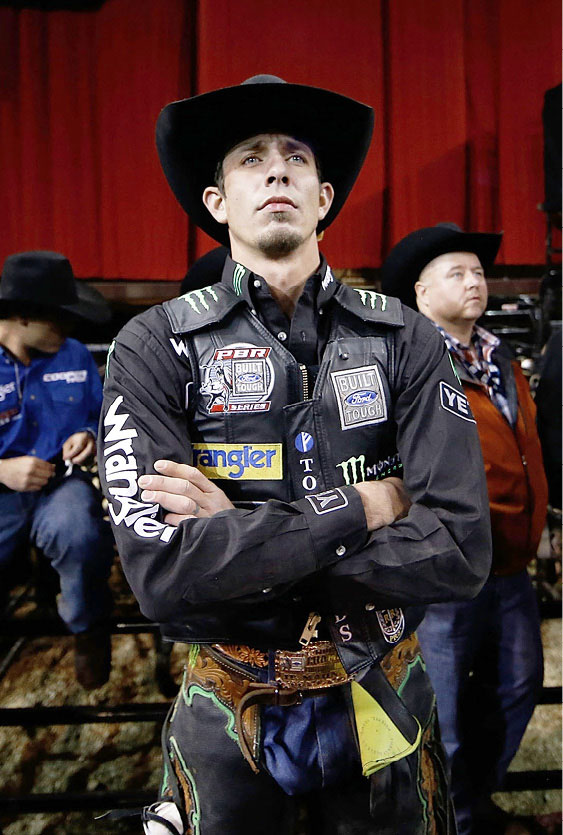

He knows no cowboy ever rode to glory on the back of a mediocre bull, so he plans to draft Air Time, 1,650 pounds of unrideable spotted fury. Bull riders have climbed on Air Time’s back 10 times this season, and Air Time has thrown them off every single time. Mauney doesn’t care about that. He has a shot at glory, and he wants Air Time to take him there.

AIR TIME SHAKES OFF SOME OF THE BEST RIDERS IN THE PBR DURING THE 2014-15 SEASON.

He hasn’t told anybody about his choice yet, but he knows once he does, the PBR world is going to freak out.

Hence the smile and the dimples.

***

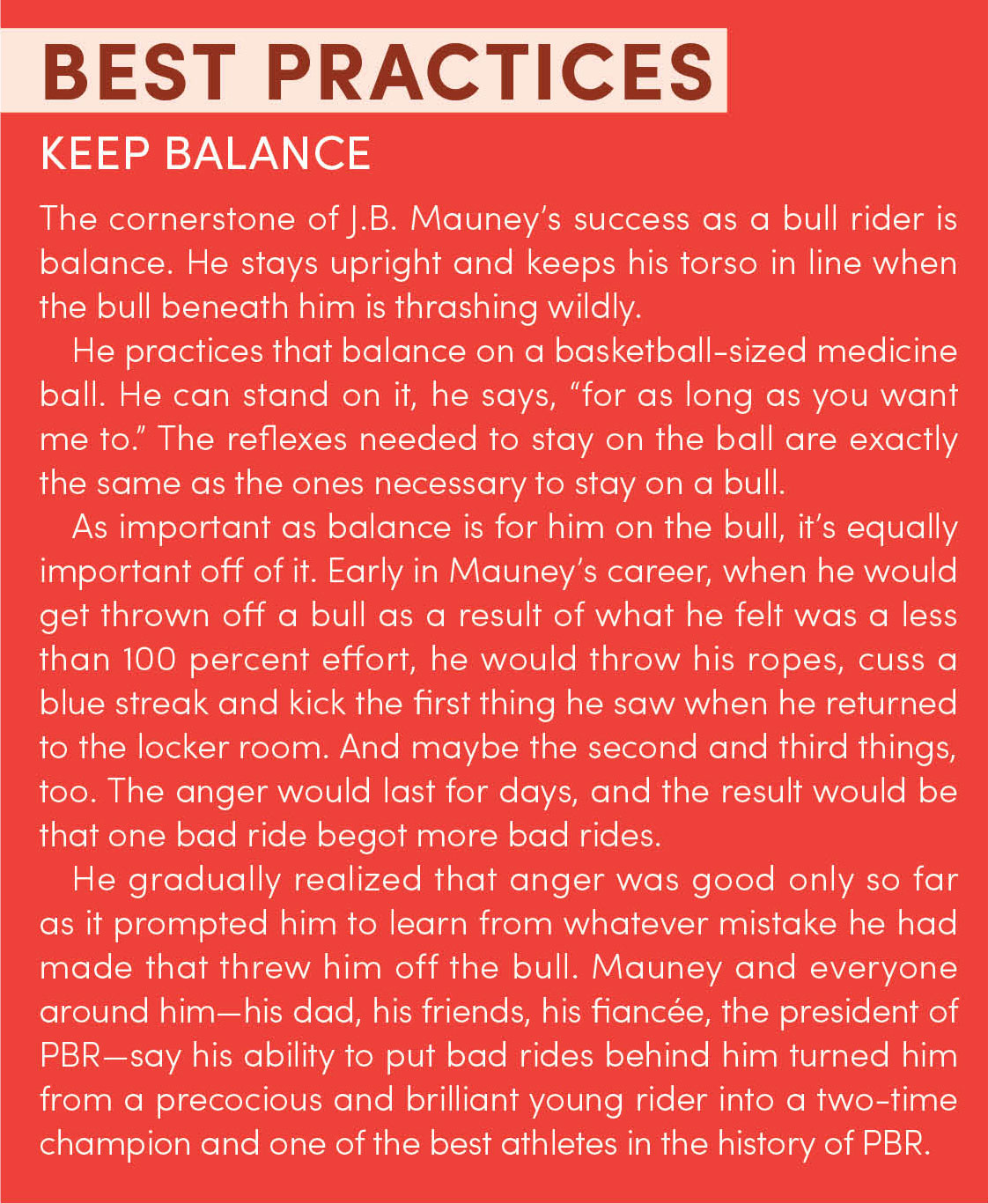

Mauney, 30, is roguishly charming, like Han Solo with chaps, a cowboy hat and a mouthful of F-bombs. He carries 140 pounds on his 5-foot-10-inch frame and wears his hair in a shaggy brown mini-mullet. When he tilts his black cowboy hat back, he reveals dancing eyes so pale blue that under the locker room lights, they look almost white. A cocky smirk lurks under those eyes, but he has earned that cockiness. He’s a two-time PBR champion who has won more money than anyone in the history of Western sports.

He grew up on a ranch just north of Charlotte, North Carolina, in the heart of NASCAR country. He started riding sheep at age 3 and progressed to horses and bulls, just as a football player goes from peewee to high school to college.

He was small as a boy and developed a nasty case of little-man syndrome. On his first day of high school, a senior picked on him on the bus, flicking his ear and mocking him for his size. When he could stand it no more, Mauney stood up, faced the senior and punched him in the jaw, breaking his own hand.

JAMES MACARI

Mauney rides with a defiant edge that he traces to moments like that. He couldn’t argue with the fact he was smaller. It was the suggestion that his size made him inferior that he meant to disprove. He can’t argue that Air Time is a fierce bull. But that doesn’t mean Mauney can’t ride him. “If you tell me I can’t do something,” he says, “watch.”

Related: 15 Qualities of Mentally Tough People

At 18, Mauney entered as many local rodeos as possible to try to win enough money so that when he went out on the PBR tour, he could stay on the road and not have to return home to work.

One night, a bull stomped on him with two hooves. Mauney knew his ribs were broken because he had broken them before. He figured all a doctor would do is wrap him in an elastic bandage, and he could do that himself. So he drove three hours to get home and went to bed. He woke up the next morning with a thing growing out of his side. He went to a doctor, who sent him to the emergency room. Doctors there told him all the ribs on his right side were broken, his liver was lacerated, and his kidneys and spleen were bruised.

Just prior to operating, a surgeon told him she didn’t understand why, after getting stomped on, Mauney didn’t stand up, dust himself off, take two steps and keel over dead. “She said my liver should have just burst. I said, ‘Well, good thing it didn’t, I guess.’ ”

Doctors told him he couldn’t ride for eight months. He went to work at a ball-bearing shop. It was hot and indoors and he was covered with grease all day, and he hated it. He lasted four months at the shop before resuming his bull riding career.

MATT CROSSMAN

He jokes he was cleared to return to competition by “Dr. Mauney.”

***

Now Mauney (pronounced moon-ey) stands behind a curtain in a hallway at the T-Mobile Arena, awaiting a press conference in the adjacent media center. He still hasn’t told anybody about Air Time. Brandon Bates, the PBR arena announcer and moderator of the press conference, peeks behind the curtain to say hello. Mauney nonchalantly mentions that there is a spotted bull he has his eye on for tomorrow’s ride. It takes a blink for Bates to realize Mauney means Air Time.

“Oh my God,” Bates says.

The dimples dig deeper. “Don’t say nothing,” he tells Bates, which is like telling Air Time not to buck. Bates lets go of the curtain and starts toward the press conference. But he turns around and slides behind the curtain again to face Mauney. He asks Mauney to announce the Air Time pick at the press conference because he knows that it will be huge news in the PBR world.

“Make it this big Rocky Balboa moment,” Bates tells him.

Bates’ instincts are spot-on. In the next 18 hours, Mauney versus Air Time will be compared to a fight between Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson and predicted to be the highest-scoring bull ride ever if he stays on, perhaps the greatest moment in PBR history.

In one simple decision, Mauney revealed the very essence of who he is as a competitor. Nobody ever remembers or cares who finished second, so Mauney is willing to try whatever it takes to finish first. And it will take one of the best rides of his life. In 10 “outs” this year, Air Time has bucked off his riders within an average of 2.73 seconds. Nobody has come close to the eight seconds required for a successful ride. But a ride on Air Time is all but guaranteed to be worth at least 90 points—the standard of excellence in bull riding in general and the specific point threshold Mauney needs to cross to give himself a shot at his third world championship.

Mauney doesn’t care about the points. In fact, when the points race comes up in the press conference, he literally sticks his fingers in his ears. Mauney selects Air Time because he’s the baddest bull, and Mauney believes himself to be the baddest rider. It will be a battle of the baddest on the sport’s biggest stage, the last round of the World Finals.

Related: 8 Daily Habits to Build Your Mental Strength

***

In his 10 years in PBR, Mauney has experienced physical maladies too numerous to list in their entirety. He regularly separates his riding (left) shoulder. He broke his riding hand in 2012 and stunned the sport by riding with the opposite hand, a decision he made in large part to prove to naysayers that he could do it.

He limps like someone with bad knees, which he has, but it’s a bad sacroiliac joint (which connects the pelvis to the spine) that causes the limp, not the knees. Either way, he has no ACL in either knee and an MCL in only one of them. Bony hypertrophy in his elbow means he can’t open his arm all the way.

Tandy Freeman, M.D., the medical director of PBR, has treated Mauney for many of those injuries and knows there are many more he hasn’t treated because Mauney hides his pain. Mauney says he was a cowboy before he was a bull rider, and the cowboy mentality is to ride if it is possible, and often when it isn’t.

In 2014 Mauney broke his leg. After examining him, Freeman told him he should get it X-rayed—but only if it would make a difference as to whether he rode the next day. Mauney didn’t bother.

Freeman taped a foam cast to his leg and Mauney never missed an event. “If you’re hurt, but you’re not crippled, you get on, and you don’t whine about it, if you can help it,” Freeman says.

Mauney tells stories about bull stomps that could have killed him in such a way that they sound hilarious. He explains his willingness to endure pain by repeating what his dad told him throughout his childhood: “If you play the game, you take the pain.”

There’s more to it than that, though. Bull riders only win money if they last eight seconds on a bull, so if they sit out, they don’t get paid. Mauney has made a record $7 million-plus in his PBR career, and he averages low to mid six figures annually in sponsorships, so he can afford to skip events, which is not the same thing as being willing to.

“There’s a fine line between being tough and being dumb, and sometimes you flirt with it riding bulls.”

As Mauney has gotten older, he has sometimes listened to Freeman’s advice that sitting out is smarter than toughing it out because it will help him in the long run. “There’s a fine line between being tough and being dumb, and sometimes you flirt with it riding bulls,” Mauney says. “It took me a long time to figure that out. I thought, riding bulls, you’ve got to be tough. If you can’t ride with pain, you don’t need to be riding bulls anyway.”

***

A few hours after the Air Time announcement, Mauney is flanked by security as he walks through the casino and into his hotel. He doesn’t stride so much as propel himself forward with a series of jerking movements. It looks painful.

We hustle into his hotel room. It’s Mauney, his fiancée Samantha Lyne, a public relations guy for WME/IMG (which owns PBR) and me. People who know both of them say Lyne, a barrel rider and daughter of a rodeo champion, is the female version of Mauney and perfect for him.

Mauney peels off his rodeo shirt, which is covered with patches of his sponsors. His physical appearance is striking. He has pectus excavatum (a caved-in chest) and he’s so skinny that you wonder whether he has to run around in the shower to get wet. Lyne pulls out a tube of pain ointment and rubs it over his lower back first, then his middle back, over the scars on his side that we’ll get to later, and finally across his shoulders, upon which he has a tattoo that reads “Born to Ride.”

Lyne shows me sleeves that normally are used for horses’ legs, which Mauney wears when he sleeps, and an extra pad that he uses on top of the mattress. He also wears gloves at night, without which his hands would swell like balloons. Despite all of these precautions, sometimes he wakes up so sore Lyne has to help him out of bed.

Mauney and Lyne were engaged a few days ago at Mauney’s home in North Carolina (they later married on January 3). He tweeted a picture from Las Vegas of her holding up the ring. She jokingly expresses doubt about whether Mauney picked out the ring himself. “Of course I picked it out,” he retorts. She is in another room when he says this. He makes eye contact with me, smiles and shakes his head, signaling he did not, in fact, pick it out.

***

For the second time this Sunday morning, it’s 2 a.m. The clock has jumped back for daylight saving time. The Air Time decision was announced about five hours ago. The ride that might burnish Mauney’s already substantial bull-riding legend is 14 or so hours in the future. Mauney orders 10 bottles of Bud Light and 10 Jägermeister shots.

“What are you drinking?” he asks Edwin Lay, a PBR competition supervisor who is sitting across from him in a casino lounge.

“Gin and tonic,” Lay says.

“Perfect!” Mauney says. “You’re getting a Bud Light and a Jäger bomb.” He goes around the table asking fellow bull riders and friends the same question and responding the same way, regardless of their answer. Eventually the drinks are assigned and a toast is made.

Someone steers the conversation to Air Time and asks Mauney whether he’s worried he made a mistake. Mauney tries to look serious. I would not say he succeeded in that.

“Do I look like a fella who worries a lot?” he asks.

***

Mauney manages to present himself promptly at 10:15 a.m. Sunday for the pre-rodeo walk down the blue carpet just outside the arena. He stops for a TV interview. He is asked whether he has a game plan to stay on Air Time after being bucked off in three previous rides. “Yeah, there’s a game plan,” he says. “Whatever I did the first three times, do not do that again.”

“If you’re hurt, but you’re not crippled, you get on, and you don’t whine about it, if you can help it.”

Mauney has a sly way of telling the truth by half-joking, and his answer reveals his philosophy that the best way to prepare is to not over-prepare. Before a ride, he tries not to think anything beyond “stay on.” He says if he thinks too much—tries to anticipate what the bull will do—he gets in trouble.

Related: 4 Questions to Calm Your Overthinking Brain

He learned this on Bushwacker, the most legendary bull in PBR history. Dubbed “the baddest body in sports” by ESPN The Magazine and “the Michael Jordan of bulls” by Newsweek, Bushwacker bucked off a record 42 consecutive riders. Yet Mauney kept picking him. Mauney finally broke Bushwacker’s streak in 2013 on his ninth attempt. And then Mauney still kept picking Bushwacker, even though he got bucked off all the rest of those times, too, because the baddest bull deserves the baddest rider. Mauney rode Bushwacker 13 times. Nobody else topped four.

JOHN LAMPARSKI/WIREIMAGE

Each ride on Bushwacker was different, and Mauney learned that anticipating a bull’s moves was the sure way to be thrown off. He says he pays attention to only a small percentage of bulls, the fiercest of all, and doesn’t want to know what they’ve done in the past because that might influence how he rides. Instead, he tries to match the bull jump for jump and relies on his own quick reactions and balance. “Think long, think wrong,” he says.

***

Before the bout with Air Time, Mauney sits with his friend and fellow bull rider Stormy Wing and four other riders in a shower area they converted into a lounge. They smoke cigarettes and tell stories. Johnny Cash plays through a speaker connected to someone’s iPhone. “I walk the line,” Cash sings, but almost every story that gets told goes over it.

One of the few repeatable stories involves the scars on Mauney’s side. In 2010, Mauney was riding a bull named Jawbreaker in Wichita, Kansas. Jawbreaker’s horn hit Mauney in the chest, which collapsed his lung. He spent a week in the hospital with tubes running through him to reinflate the lung. He could have died—or in the very least been forced to quit riding—but now he’s laughing, teasing the bull rider sitting next to him, Kasey Hayes, because Hayes lives in Kansas and never visited him in the hospital. This seems to epitomize Mauney’s view of life: If it doesn’t kill you, it makes you better, tougher—badder. By now stories like this only add to his legend. He knows a bull rider’s career is short—he only has a few years—so he’s going to pack as much into those years as he can.

A bearded man wearing a headset pokes his head in and says introductions start in one minute. The iPhone blares AC/DC’s “For Those About to Rock.”

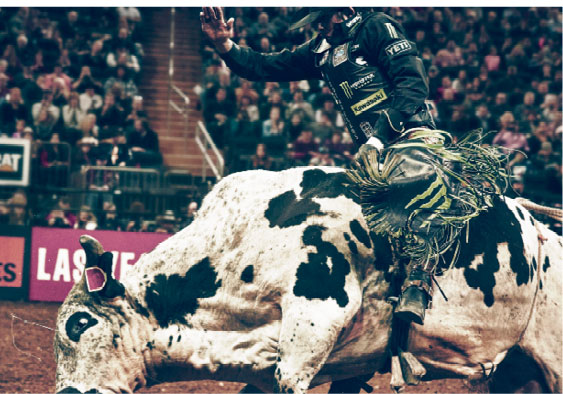

Now, finally, comes Mauney versus Air Time. The battle between this pain-defying beast of a man and this pain-inflicting beast of a bull is one of the most anticipated rides in PBR history, and it is unbelievably, massively, comically anticlimactic.

JAMES MACARI

Shortly after leaving the chute, Air Time bucks into the metal fence that separates the arena floor from the stands. The collision changes the bull’s trajectory, which changes Mauney’s trajectory. He flies off the bull and crashes hard onto the dirt.

Mauney has barely landed when PBR officials throw re-ride flags onto the ground. Those flags signal a do-over and are common when a bull hits the metal fence.

Mauney scrambles away from Air Time and the pulverizing stomps of his hooves. Mauney’s left arm and hand are numb and his shoulder screams with pain. After Air Time’s collision with the fence, Mauney’s shoulder “subluxed,” meaning it popped out and popped right back in. This has happened to Mauney several times, including at least twice in the past two months.

Mauney knows simply tightening the ropes for his re-ride could pop his shoulder out again. But he’s going to re-ride anyway. Nobody remembers a rider who couldn’t go on. “Ninety-nine percent of the people in the world would not be able, five minutes later, to even try,” Freeman says.

JAMES MACARI

The rules say the re-ride has to come on another bull. Mauney picks Stone Sober, which he had ridden for 92.5 points recently in Nampa, Idaho.

Wing ties the ropes around Stone Sober to give Mauney’s shoulder a break. Mauney waits under the stands behind the chute platform. I look down and see him lose his footing on uneven dirt, like when you encounter a step down you didn’t know was there. I see pain shoot through him, as if someone yanked a nerve-zipper from his feet to his neck. My face must have betrayed something about how brutal that appeared because when he sees me looking at him, he shrugs with a helpless expression. He leans across a metal bar, takes his hat off, rubs his hands through his hair and tries to catch his breath.

A few minutes later, Mauney’s walk-up music—“Bad to the Bone” by George Thorogood and the Destroyers—blares over the loudspeaker. Mauney climbs onto Stone Sober. He completes his pre-race routine—whacks himself in the leg, slaps himself in the face, nods his head—and flies out the chute. The seconds ticks off, one after another, and the crowd roars when he is still atop Stone Sober as the horn sounds after eight seconds.

A legend, delayed though it may have been, is born.

But something is wrong. A hush follows the crowd’s explosion, like when a football crowd knows a touchdown will be examined on instant replay. The announcers say the ride is under review.

Mauney grabs his rope, walks off of the arena floor and sits on the dirt. One key to a successful ride, Mauney told me a few days earlier, is to “get up where the business is at,” and by that he means lean into the buck, like a bicyclist crouching over the handlebars. A replay shows that during one buck, Mauney leaned far forward, turning his body into a rag-dolling figure 7. Mauney’s free hand appeared to glance off of the bull’s shoulder—and any touch of the bull with the free hand means an automatic zero-point score.

When the announcement of the zero is made, Mauney storms off. The bell on his rope bounces behind him.

***

I see Mauney later in the casino lounge where he held court into the wee hours this morning. He’s in a good enough mood to be out with Lyne, friends and fellow bull riders. He doesn’t know if he touched Stone Sober. “I’m not saying I touched it, and I’m not saying I didn’t,” he says. “If I slapped that bull, I’d be the first to tell you that I did.”

Failing is a predictable byproduct of his approach, and he accepts that. He never regrets decisions like the one to ride Air Time. The only time he second-guesses himself is when he believes his effort was less than total.

In one of his jokes that is also partially true, he imagines himself, years from now, stuck in bed, his body mangled from years of bull riding. All he’ll have to do all day long is lie there and think about the good old days.

The way he sees it, if making those memories leaves him in that condition, they better be worth it.

Related: If It Doesn’t Suck, It’s Not Worth Doing

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.