Guy Fieri puts his knuckles down on a piece of squash.

This is how I’m supposed to hold my fingers while chopping. He stops to explain: “If you cut this part of your finger, it’s going to hurt a lot,” he says, pointing to the flat part of his knuckle. “But if you cut the tip—well, that’s gonna hurt a lot more, and we might have to rush you to the hospital to see if they can reattach it.”

Then he demonstrates the technique for me. Except he chops so fast, it’s just a blur of steel and squash, with slices falling off at machine-gun pace. When he’s done, I notice that the other people standing around watching are impressed, too, like he just performed a magic trick with a lethal weapon. Say what you will about Guy Fieri, the man is good with a knife.

Related: Guy Fieri’s 5 Quick, Shocking, Life-Changing, Easy Cooking Hacks

I’m not. My chops are slow and uneven. My fingers almost immediately revert to their earlier, more dangerous, grip. He slices four or five pieces in the time it takes me to finish one. He tries to guide me—“Hold the knife up here, like this… Watch those fingers… Turn it upside down and scrape like this so you don’t dull the blade”—and I get a little better. When my right sleeve slides down to my wrist, he jokes: “Yeah, you want to get that sweater right in there in the food.”

The next lesson is about salt. He says it’s “the most overused and underused ingredient in cooking today.” And before I can ask him to elaborate, he has me grabbing generous pinches of salt with both hands and sprinkling it all over everything in front of us: the asparagus and squash and zucchini and mushrooms and chicken.

He expounds upon the value of freshly squeezed lemon juice—which he simply calls “acid”—and the difference between fresh ground pepper and the pre-ground kind. He keeps his black peppercorns in a Turkish coffee grinder. He cranks some into his hand and then lifts it to take in the aroma. He nods. Then he does the same thing with a bit of the pre-ground, but shakes his head and grimaces.

“The difference is incredible,” he says. Then: “I’m not even sure why I have this crap,” before chucking the entire plastic container into the garbage can.

We’re standing in the commercial-size open-air kitchen in his Northern California backyard, and he’s giving me an impromptu cooking lesson. This is Fieri in his natural element. The crew from a photo shoot earlier in the day is still hanging around, talking and laughing. He’s got several dishes in the works and more food standing by just in case. He’s turning from the stove to the pizza oven and back, all while holding a flowing, engaging conversation about the food and about life.

As we’re pulling apart the beautiful fresh Swiss chard—he’d stressed several times the importance of pulling instead of chopping whenever possible—I ask if he ever gets nervous cooking.

“Do you get nervous writing?” he asks.

“I don’t usually have to write in front of a bunch of strangers,” I say.

“Cooking is all about people,” he says. “Food is maybe the only universal thing that really has the power to bring everyone together. No matter what culture, everywhere around the world, people get together to eat.”

His diehard fans know about his background, about his fast rise to fame, his many TV shows, 40-something restaurants and five books. They might buy his line of sauces at the grocery store or use his brand of knives or cookware. They may even drink his new high-end wine. But when most people hear the name Guy Fieri, they think of his show about diners and dives. They think of those TGI Fridays’ commercials he did a few years ago. And they think of his face and hair, with the frosted tips and goatee. He’s famous enough now that plenty of people don’t like him for reasons they can’t even articulate. The truth is, he’s someone who could live in your neighborhood.

Related: 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Guy Fieri

In the world of food and wine, snobbery and affectation often substitute for status. But Fieri is as unpretentious as it gets. The cargo shorts, the T-shirts, the tattoos and goofy jokes. He likes what he likes. Even in that first audition tape he sent in to the Food Network 10 years ago, Fieri said he was about “real food for real people.” He’s built his empire by being himself. By not caring what his detractors think. By not changing for critics. He has the same friends he had before he was famous. They have nicknames like “Mustard” and “Dirty” and “Possum” and “The Spaniard.” Fieri’s friends mostly call him “Guido.”

As we sauté the vegetables, Fieri explains that there are only two ways to cook something: “Really fast, or really slow.” Anything in between, he says, is “mediocre.” He encourages me to taste the food as we cook, to add salt and pepper as needed. “And you can’t forget the acid,” he says, squeezing a lemon over the pan.

***

His only two goals in life were to own his own restaurant and to be a good father. “My dad’s my best friend,” he says. “So being a good father to Hunter and Ryder, spending time with them and teaching them, that’s No. 1 for me.”

Fieri, now 48, estimates that, if he weren’t so focused on being there in the morning when his younger son wakes up and at night when he goes to sleep, he could do 25 to 35 percent more business—an astonishing number when you consider the incredible amount Fieri actually does. (His older son started college last fall at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, following in Fieri’s footsteps.)

But his aunts knew when he was a kid that he was destined for something different. When his family got together for big dinners, young Fieri was always the entertainment. He’d tell jokes or stories with over-the-top descriptions and big gesticulations. They told him they thought he’d be in movies or on TV one day.

He started cooking because, he says, in his family’s home, whoever cooked got to decide what the family ate that night, and he liked deciding. (His parents went through a phase in the late ’70s that included feeding him “enough steamed fish to kill a kid.”) He says cooking was a life skill that his father taught him, along the lines of how to change a tire.

In middle school he had his own company, a pretzel cart he called “The Awesome Pretzel Cart.” In high school he spent a year studying abroad in France. At UNLV, where he majored in hotel administration, he spent a few years in corporate restaurant jobs.

Through the years, he witnessed the power of food. Not just the way it seemed to fuel relationships, but the way it can rejuvenate people or turn a bad day into a good one. He cooked for his extended family and his friends and total strangers he invited over for dinner, a surprisingly common occurrence according to the people around him. When his younger sister was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago, he cooked for her throughout her treatment, creating vegetarian dishes to suit her diet. (A recipe for “Morgan’s Veggie Patties” is still up on the Food Network website.) When she died, he cooked for the family as they grieved.

Not long after that, The New York Times ran a cartoonishly scathing review of Fieri’s restaurant venture in Times Square, printed in the form of an open letter to Fieri written entirely in questions.

Despite his reputation, he says a lot of the same things other celebrity chefs and food authors say: Meat shouldn’t be the center of a meal; avoid most sweets; just say no to soda; eat local and organic whenever possible. Most of the vegetables he cooks come from his own garden.

At the moment, that garden is behind the same 1,700-square-foot house he bought 20 years ago, long before the television fame. He and his father built the outdoor kitchen and renovated the backyard, and they expanded the garages to make room for his growing collection of classic cars, trucks and hot rods. A few years ago, he built a house next door for his parents. They come over for dinner three or four times a week. The first true test of a new dish, he says, is whether his mom wants to take home leftovers.

“When she doesn’t want to take some for later,” he says, “I know it’s no good.”

***

Fieri’s three-minute Food Network video opens with Fieri wearing a red bowling shirt and leaning against a bar. He looks mostly the same as he does today, with a sunglasses-shaped burn on his cheeks and a smile.

“Hi, I’m Guy Fieri and welcome to Sonoma County, California, home of true wine country cuisine,” he starts. “Today I’m going to prepare a dish for you, not in fusion, but in confusion. I’m gonna do a gorgonzola-tofu-sausage terrine served over a mildly poached ostrich egg. Now, because we’re in the wine country, I’ll be serving that over Grape Nuts, and done with a delicious pickled herring mousse right on top.” He clutches his hands together in front of his chest and adds, “It sends shivers up my spine!”

His only two goals in life were to own his own restaurant and to be a good father.

Then he pauses, looking at the camera for a second, before bursting into uproarious laughter. He says he’d like to teach people about “real food for real people.” He says cooking should be about sparking the imagination. As he starts walking, the camera follows. He stops at a cutting board and explains that what he’s really going to make today is a combination of sushi and Southern-style barbecue.

“In Japanese, sushi does not mean raw fish,” he says. “It means seasoned rice.”

He quickly puts together a sushi roll stuffed with a piece of pork, a piece of avocado and a french fry, while telling the story of the dish’s name. He says a friend told him, “You can’t make sushi out of barbecue,” and called him a jackass. “So that’s what we call it, the Jackass Roll.”

Before the video is over, he says his name one more time for the camera: “My name is Guy Fieri. My friends call me Guido. You can now consider me your friend.”

This was the spring of 2006. By then a restaurant customer and family members had noted his star potential. His friends had seen ads for The Next Food Network Star, an Apprentice-style game show where the winner would receive a contract to host six episodes of a cooking show. It took some convincing, but Fieri sent in his DVD in the last week before the deadline. When the call came, two days later, he first thought it was a prank his buddies were playing.

“When she paused and apologized for mangling my last name, I thought maybe this is real.” (For the record, it’s pronounced Fee-EDDY.)

Within a week he had a producer at his house, interviewing him on camera. He flew to New York to tape the show. His wife, Lori, was eight months pregnant at the time with Ryder. Every day, producers would demand the contestants turn over their cellphones. And every day, Fieri would bring two phones: one to turn in, and one he could use if needed.

On the air, he was relaxed, funny—the same way he acts hanging out with his friends and family. It made him accessible to viewers, especially men, an audience other shows on the network struggled with.

After he won that contest, fame came quickly. His cooking show, Guy’s Big Bite, premiered a few months later. Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives—what he affectionately calls “Triple D”—came the next year. Low-brow though it may seem, Fieri is a patron saint to the dozens of restaurateurs he’s featured on the show, who often double or triple their business within weeks of their first airing.

The year after that the network gave him a third show, Guy Off the Hook, with a live studio audience. Then came a game show, Minute to Win It, which lasted two seasons on NBC. And a few years later he won an Emmy for a special he recorded called Guy’s Family Reunion. (He keeps his statue on the kitchen counter.)

The commercials started around 2008, less than two years after he sent in that video. In addition to the Fridays’ campaign, he also recorded ads for Flowmaster mufflers and Aflac. He opened new restaurants in Las Vegas and New York and signed deals to sell burgers on a cruise line, and to brand all manner of kitchen-related products. Few people in history have been able to monetize their names as well as Fieri has. And everything he’s sold has a similar feel. A Guy! signature has meant that it’s for the masses, for real people, not for the snobs.

That’s what makes his new wine label, Hunt & Ryde, seem so different. Each bottle retails for between $40 and $75 and there are a limited number of cases available. Still, Fieri insists the wine is meant to be consumed. He says the project, part of a partnership with a local winemaker Guy Davis, is something he’d like to leave his sons, Hunter and Ryder.

“Putting their names on this makes it one of the most important things I’ve ever done,” he says. That’s why he’s promoting it the way he is. That’s why he’s opening himself up to even more criticism.

***

When the pizzas come out of the oven, a small crowd gathers to see what we’ve made. Fieri slams a pizza cutter into the edge of the crust and leans on it as he slices each small pie into sixths. As the pieces go out, the reviews are positive. The dough I tossed isn’t perfect, but nobody complains. The veggies we chopped and sautéed are just the right texture. You wouldn’t call it the finest fare ever assembled, but it’s almost certainly the nicest lunch I’ve ever had a hand (or sleeve) in making.

Soon the hungry strangers are satiated, and Fieri is cranking Ozzy Osbourne through his outdoor speakers. He takes a moment to quietly survey the scene as the crew collects the camera equipment and heads out. He insists that anyone who lives locally must pack leftovers. (There are several takers.)

At some point Lori comes outside to find a dozen strangers in her backyard and doesn’t seem remotely surprised. She jokes that she’s hosted crews much bigger than this in the house plenty of times. This is part of life being married to Guy Fieri.

When everyone else is gone, he invites me inside to talk a little more. The space was clearly designed to entertain, with a long bar and a table that can seat 20. In the corner is a giant wooden Buddha statue and on the walls are photos and souvenirs from various trips and adventures. (On the wall of his garage, former Los Angeles Rams quarterback Vince Ferragamo has sketched and autographed the play that sent his team to Super Bowl XIV.)

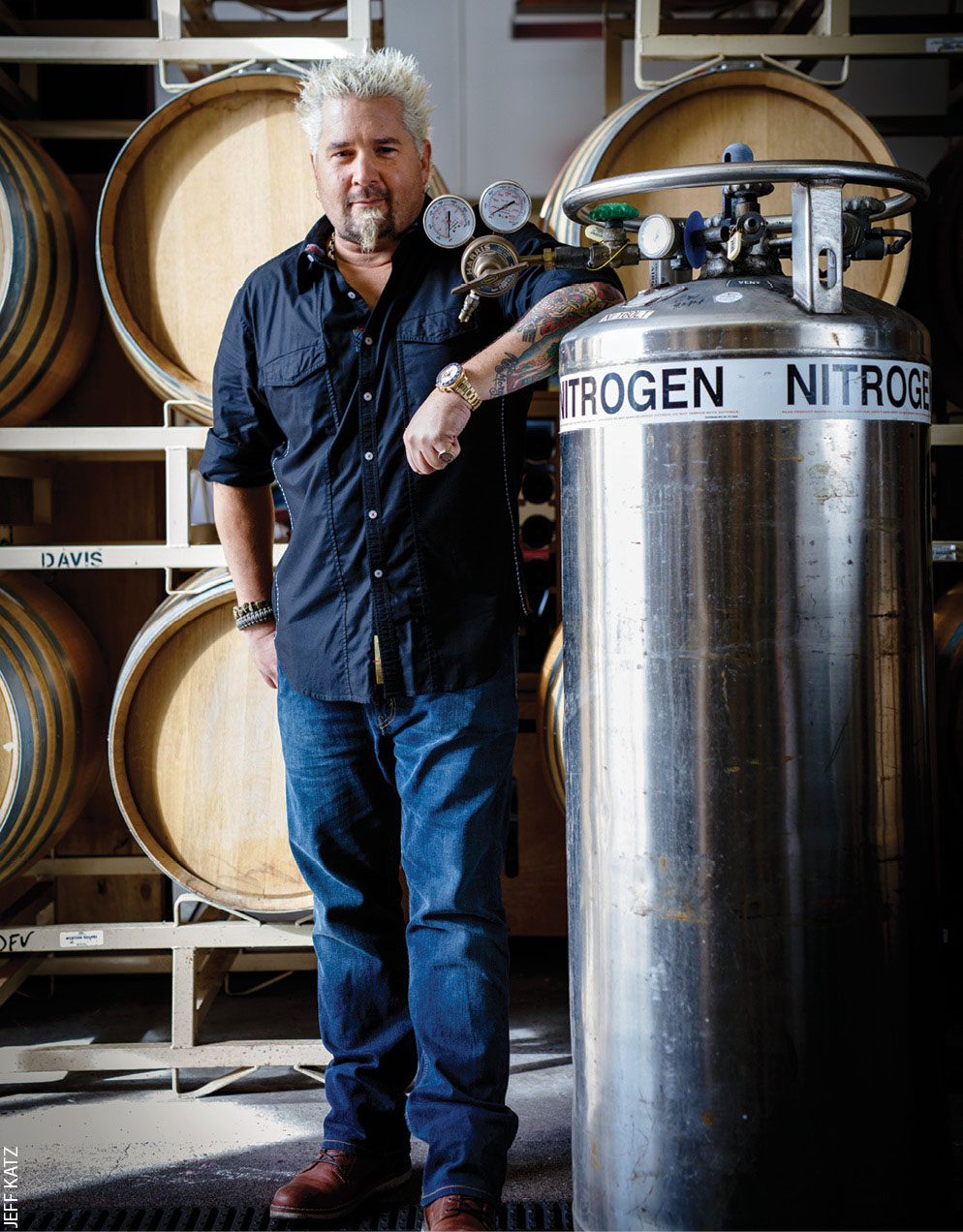

He offers me coffee, tea, a nip of something stronger. So far today I’ve been with him between five and six hours. I’ve watched him pose for two photo shoots: one at Davis Family Vineyards, where he sells his wine, and one in his garage, where he held a giant fork and made a series of fork-related puns. I watched him taste some of the pinot noir he’ll bottle later this year. I rode shotgun in his muddy king-cab pickup truck as we drove through Sonoma Valley, and along the snaking Russian River, and he extolled the virtues of fatherhood. Then there was the cooking lesson, where he patiently demonstrated everything down to the proper asparagus-breaking technique.

He is who he is, all day long. “What you see is what you get with me. There’s no show.”

Now it’s quiet, though. He’s telling me about a recent special he shot in Europe when Ryder returns home from school. Fieri cuts himself off midsentence to call out. The boy walks over to where his father’s sitting and he gives him a hug before heading off to do his homework.

When we pick back up, the conversation somehow turns to how he deals with the negativity fame has brought him. Ten years ago he was a restaurant owner whom most of us had never heard of. Now he’s fodder for late-night talk show jokes.

“I’m like anybody else,” he says. “You get enough, you can get beat up. You can get hurt. You can get frustrated. You can get demoralized.”

He says he doesn’t think about it much, but when he does, the level of hate baffles him. “If there are 100 people who don’t like me, 90 of them don’t have a reason, Have I pissed some people off? Yes. Have I done wrong? I’m not sitting here saying I haven’t. But most of the negativity is entirely superficial.”

“What you see is what you get with me. There’s no show.”

He adds: “What am I supposed to do? Am I supposed to stop being me? If someone boos a quarterback, does that mean he stops throwing his favorite pass?”

Related: ‘Embrace the People Who Tell You You’re Full of Crap’

It breaks down like this, he says. “If I probably didn’t have tattoos, or if I probably didn’t bleach my hair, or if I probably didn’t wear blue jeans and a T-shirt to fancy things, if I didn’t do things that make me look like someone who’s whacked out of their mind, it’d probably be different. But then again, that’s how I wanna dress. And I like my tattoos. And I like my hair cut the way it is.”

He says he can’t pay attention to critics, not when he has so much he loves in this world, so many people he considers friends. There are too many moments like that hug from his son.

“We did a lot of fun things today,” he says. “But that was the highlight of my day.”

Fieri says he does sometimes look forward to a day when he isn’t in the public eye so much, when he can go back to doing what he loves most.

“I’m gonna open a small restaurant on the beach in Mexico,” he says. “We’re only gonna have a few tables and we’re only gonna cook what’s fresh that day. We’re gonna get back to the basics.” He looks up, thinking about his dream.

“Real food for real people.”

Related: Ep. 10: Be Confident Like Guy Fieri

This article originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine.