I was raised in a stable middle-class family in central Florida. My brother and I rode our bikes to school, went to church on Sundays, and were tucked in bed by 7:30 p.m. sharp.We led a routine, predictable life, and I grew up thinking everyone lived this way. I was also taught to believe some specific things about life, most memorably that certain people always tell the truth and are always right: parents, police, and priests.

Uh-oh.

Do parents always tell the truth? Nope. Do police officers? Unfortunately, that isn’t the case.Are all priests trustworthy? Horrifyingly not.

This was a limited paradigm, or mindset. Paradigms are the lenses through which we view the world, based on how we were raised, indoctrinated, and trained to see everything in front of us. We all wear these metaphorical pairs of glasses, and they vary in accuracy. They might be the right prescription or slightly off. In some cases, you might have a metaphorical cataract.

Mostly our mindsets are unconscious or subconscious. None of us (hopefully) set out in the morning to have biases or prejudices, but every one of us has them deeply ingrained in us from our experiences while we were raised. We often aren’t even aware of them or their ongoing impact—negative and positive.

With the “parents, police, and priests” paradigm, I fortunately didn’t have to put it to the test. I was generally surrounded by good examples of all three, but if I hadn’t been so lucky, this paradigm could have caused serious damage. As it was, I didn’t realize that parents were actually real people with flaws and weaknesses until my mid-twenties.

And it wasn’t until I was in my thirties that I understood that leaders are people too—that they don’t make all the right decisions or have all the right answers.

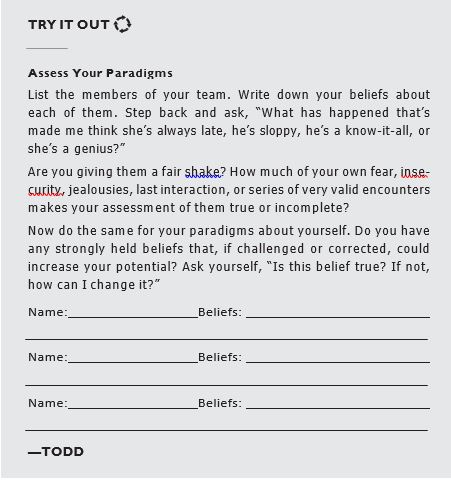

Your job as a leader is to continually assess your paradigms for ac- curacy and ensure they reflect reality. So ask yourself what you believe about leadership, your team, and yourself. Maybe you believe that the colleagues who think like you are “high potentials” and those who challenge you aren’t. Perhaps you believe you’re not really leadership material and someday everyone will find out.

The See-Do-Get Cycle

I once went skiing with a good friend at Snowbird, a popular resort in Utah. Although she’d never skied down anything steeper than a bunny slope, I somehow convinced her that she could handle the Black Diamond run.“Come on, come on, come on!” I urged her.“No problem. Black Diamond! Woo-hoo!” And after luring her to the top, I gave her an encouraging shove.

She was taken down on a stretcher.

Horrified, I recently realized that I do this in my leadership role too. (And don’t worry, my friend wasn’t seriously injured and bounced back, no worse for the wear, although she’s never skied again, at least with me.) While many leaders lack confidence in their people and tamp them down, I’m the opposite: I believe anyone can do anything if I just provide enough encouragement. I paint the vision and create excitement—whatever it takes to inspire them to my degree of confidence in them. My intention is to help people achieve their full potential . . . and who cares if they agree?

This paradigm sometimes works. But sometimes I accidentally lure people into terrible Black Diamond experiences instead. “No, you actually can do this. It’s easy. It’s only a speech to two thousand people. You’ll do just fine.”

When I’m putting people into jobs, assigning them to new territories or countries, putting them on stages in front of two thousand people, and contracting high-paying consulting gigs for them, the stakes are high. At worst, this paradigm can destroy people’s confidences, reputations, and even careers, if we’re not aligned.

I often need to rethink my approach and remember something we teach at FranklinCovey: the See-Do-Get Cycle. It’s the root of real behavior change. When you challenge your mindset (tough work, by the way) you can make lasting changes to your actions and your results.

To best understand this cycle, let’s start with our desired result, the “Get” part of the cycle.We all have different outcomes we’re trying to achieve: improved health, meaningful relationships, financial stability, influence in our communities and careers—as well as short-term results we want from our day, meeting, or project.

What drives those results (Get) are our behaviors, the “Do” in this cycle. It’s how we act. If we want to complete a report by the deadline, then we have to behave in a certain way throughout the day: check with the finance department about last quarter’s profit and loss statement, resist distractions, etc. If we want to build rapport with our co-workers, we can invite them out to lunch. If we want to nail our presentation, we practice it over and over. You get the point.

Most people see that behavior and results are interconnected: what we do drives what we get. That is not an epiphany.

Here’s what I think most people don’t appreciate: the first crucial step, “See.” This means that beyond our behavior, our results are affected by our mindset.

How we see things affects our behavior, which in turn affects our results.

Paradigm. Behavior.

Result. See. Do. Get.

Listen to the excerpt here!

If you want to get short-term results, change your behavior. You’ll stop smoking—until a tense day at work. You’ll wake up at 5 a.m. through sheer willpower—once, then hit snooze the rest of the week. You’ll stop swearing—until you get cut off in traffic. Behavior changes will only net you a temporary fix.

As Dr. Stephen R. Covey taught, if you want to fundamentally change your results, if you want long-term sustainable impact, you have to challenge your mindset.

Having identified my “Black Diamond” paradigm, I wasn’t happy with it. Sometimes it works, but not often enough—and my friend hanging up her skis made me rethink it. I reevaluated my paradigm about setting people up for success (See). Instead of relying on woo-hoos and enthusiasm, I help my team members develop their skills . . . after giving them a chance to opt out of my grand plans (Do). As a result, I’ve learned to grow people who are actually willing and ready (Get), and fortunately decreased the number of people I push down ski slopes.

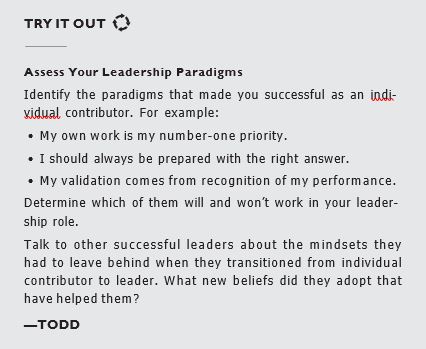

From Individual Contributor to Leader

In tennis, what wins on grass and clay doesn’t always translate to asphalt. When you win Wimbledon, you don’t expect your coach’s first conversation to be, “Congratulations, you won on grass! But now it’s going to take a whole different approach to win on asphalt.” You expect to be showered with accolades; instead you get an ego enema.The world of professional tennis is fraught with experts who were unable to transfer their superior play from one surface to another.

Likewise, I don’t imagine that most high-performing, driven people promoted into leadership realize that they must now fundamentally change their approach. But many of the paradigms that got you promoted won’t make you successful as a leader. You may be aware of Gallup’s bestselling book Now, Discover Your Strengths. A subsequent book, Dis cover Your Sales Strengths, highlighted the conundrum high-producing salespeople face when they are “rewarded” with a promotion to become a sales leader. The strengths they perfected as an individual salesperson often included a strong sense of competition, a need for individual recognition and fame, and sometimes a zero-sum-game mentality—I win; they lose. Great for winning on the sales scoreboard, not so great for nurturing, coaching, and leading your team (as in, those people who might have been your peers yesterday).

Across most professions, this perilous chasm exists: teacher to principal, server to restaurant manager, physician to chief of medicine. Or as the bestselling book by Marshall Goldsmith states, What Got You Here Won’t Get You There. Fundamentally, becoming a leader will require you to let go of some of the skills and mindsets that made you successful as an individual contributor.

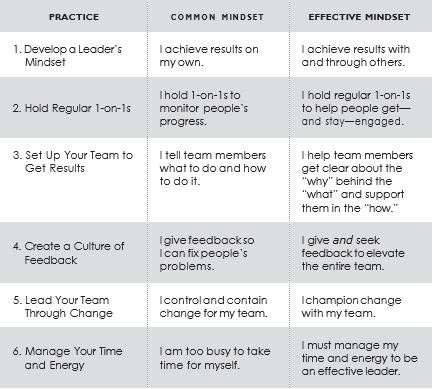

In the best of worlds, your manager would sit you down, talk about your strengths and why you were promoted, then explain what you’re going to need to do differently going forward. If you don’t receive that feedback, you have this book.We’ll introduce each of the practices with a key mindset shift leaders must make to accomplish results. Circle which one tends to describe you at this point in time. (Don’t know? Ask your team—they’ll definitely have an opinion.)

Practice 1 Mindset Shift

I once worked with a record-setting salesperson, Carolyn. When a sales-manager position opened up, it was a no-brainer to promote her. Everybody assumed she would seamlessly transition from hitting—and often exceeding—her number quarter after quarter to helping her new team do the same.

That didn’t happen. Instead, if her salespeople faltered during a client meeting, Carolyn would swoop in and use her extraordinary sales skills to close the deal. She thought she was saving the day. She was, but only that day. Her team didn’t develop their own selling skills because Carolyn wouldn’t let them make mistakes and recover from them. This is a common new-manager mistake: relying on your individual contributor skills—and doing everything yourself as soon as there is a problem—rather than helping your team solve the problem and learn. In the process, you lose your new team’s trust. Carolyn was so focused on helping get the sale, what she knew she was good at and could do, that she lost sight of a critical reality: her new role was no longer about her hitting the number—it was to have her team hit the number.

What if Carolyn didn’t save the day during sales meetings? Yes, her team would make mistakes. Some deals might not close. But her team would learn from those errors, especially if she followed up with feedback and coaching, and they would probably get better results in the future. Just as important, she would show that she trusted her team, rather than treat them like rookies who needed hand-holding. The result would be savvier, more skilled, and confident salespeople who collectively met their numbers (and weren’t reliant on one person to save the day every time).

When you become a leader, your definition of results needs to change. You need to see them differently. When you were an individual contributor, your results were the work you did. But now you’re a first- level leader, so you own the results of everybody on your team. Your first job is not to get results alone, but with and through others. You’re still responsible for your personal deliverables, but they take a back seat to ensuring that your direct reports hit theirs, while the people on your team grow, learn, and even become leaders themselves. In other words: your people are your results.

If you have the common mindset of achieving results on your own, it’s important to accept once and for all that your work isn’t just about you anymore; it’s about them. It’s time to let go of your past successes. You earned the leader’s chair because you performed at a superior level. Take a victory lap. Now, let it all go and focus on the job ahead.

From EVERYONE DESERVES A GREAT MANAGER by Scott Jeffrey Miller with Todd Davis and Victoria Roos Olsson. Copyright © 2019 by Franklin Covey Co. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Photo by Jacob Lund / Shutterstock.com