By his 20s, Aaron LaPedis, gallery owner and author of The Garage Sale Millionaire, was earning more money than his father, a high-level federal employee, by buying and selling art and coins. He drove a pricey BMW, spent lavishly on meals and travel, attended swanky charity events in his hometown of Denver, and was frequently covered in regional newspapers.

“I once gave a tongue lashing to a writer because I didn’t like the placement of the article,” he says. “Can you imagine? I said, ‘You gave me page left. I wanted page right! And the picture was too small!’ ”

Cocky? You bet he was.

So was Vannessa Wade, founder of Connect the Dots Public Relations in Houston, who, by the time she graduated from college, was pretty sure she knew… well, just about everything. “It’s hard not to have confidence when you grow up in a household that wants you to strive for the best. If we felt we could fly off the top of the house, my father encouraged it,” she says.

“I believed that if you believe in yourself and do all the right things, everything’s going to fall into place,” Wade says. “I would go into jobs with that mentality. I had experience; I was young and fresh—why am I not CEO after two weeks of working? I felt promotions should have come faster.”

Even when a mentor suggested she tone it down, Wade didn’t get it. “I thought I was just providing information. I viewed it as giving every detail I thought you would need to help me go higher and further in life.”

Levi King, CEO of San Mateo, California-based Nav, a website that provides free scores and other tools for small businesses seeking credit, was also a 20-something wunderkind and considered himself a master communicator. “I didn’t sugarcoat anything. I would tell it like it is.” He remained confident when a serious disagreement with a business partner led to a 360 feedback survey of their employees.

“If there was ever a time in my life that I thought I would be absolutely vindicated… I would have put money on it,” King says. So he was shocked when about 100 people ranked him a two or three out of a possible 10 on communication skills. “It was painful. For about a week, I stewed. My natural reaction was These guys are all idiots. Somehow everyone around me was wrong.”

Related: How to Overcome the Fear of Feedback

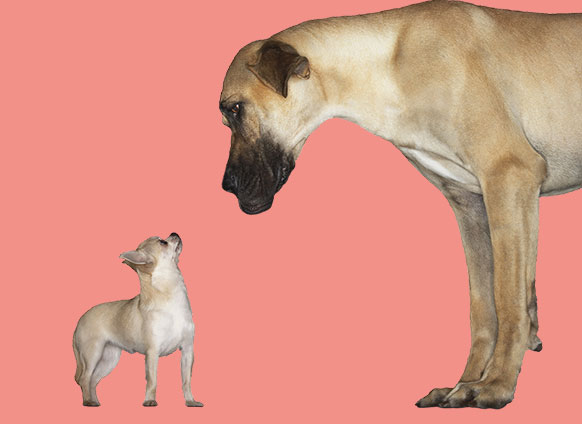

Cockiness is one of those things that is easier for others to see than to see in yourself.

And although self-confidence is something to aspire to, cockiness can be detrimental to your career and relationships.

A Big Difference

“Cockiness is not authentic. It’s based in insecurity.”

“Confidence comes from a very authentic place, a very whole place,” says life coach Valorie Burton, author of Successful Women Speak Differently: 9 Habits That Build Confidence, Courage, and Influence. “You believe in your abilities to do something. You show up in a very secure way. Cockiness is not authentic. It’s based in insecurity. It’s more about making other people think you’re confident as opposed to being confident.”

Jennifer Kahnweiler, leadership consultant and author of The Genius of Opposites: How Introverts and Extroverts Achieve Extraordinary Results Together, says cockiness is the opposite of humility. “To me cockiness indicates a lack of self-confidence.”

Scholarly research doesn’t use the term cocky, but Deborah Feltz, who chairs the sports psychology department at Michigan State University, equates it with overconfidence. Researchers such as Feltz speak in terms of self-efficacy, or “the belief that one can be successful at a certain task. How confident am I, from zero to 100 percent, that I can putt my ball into the hole within two putts, for example. Cockiness on that continuum is at the extreme—I’m 100 percent confident.”

And Jacob DeLaRosa, chief of cardiac surgery at Portneuf Medical Center in Pocatello, Idaho, teaches the difference to young doctors. “You are confident because you know the facts, and you know the data, and you’re well-read,” he says—while knowing that, even so, things might not pan out. It’s a lesson DeLaRosa learned early in his medical training, after he saved a burn victim’s life. “One of the senior residents told me, ‘Be very careful, Dr. DeLaRosa, about being cocky. For every life you save, there will be two that you won’t be able to.’ The two that you didn’t get, that’s part of the humility that’s needed in medicine.”

Related: 6 Attributes of Healthy Humility

How Cockiness Hurts Us

In medicine, overconfidence can cause doctors to make decisions that are not in the best interest of the patient, DeLaRosa says. “Sometimes it’s knowing when not to operate.”

Cocky people might also make more mistakes, Burton says. “They might start getting a little sloppy because of their overconfidence and lack of humility. You’re less likely to admit mistakes and less humble about learning and growing because you think you’ve already arrived.”

Data actually supports this theory in sports. “Where overconfidence can get you in trouble is when you aren’t realizing your fallibilities, your limitations, your need to improve,” Feltz says. “You think, I’ve got this in the bag. There is data connecting with that lesser performance.”

LaPedis sees now how overconfidence led him to unwise decisions. “Everything I did was successful except for the stock market, and I lost a lot of money,” he says. “There was a day I lost $100,000. Something like that should have bothered me more, and that’s where I think I made my biggest mistakes. I did not let it affect me enough. I never prepared myself for failure.” Although he was worth millions at the end of 2007, he had neglected to set aside retirement savings, he had his wife put her savings into his investments, and then he was entirely unprepared for the economic downturn that hit in 2008.

“Cocky people burn bridges, don’t give others enough credit and are generally annoying.”

Cockiness can interfere with relationships, too. Although people are drawn to the inclusive vibe of confidence, cockiness is off-putting, Burton says. “Cocky people burn bridges, don’t give others enough credit and are generally annoying. Although cockiness can open doors for some people, it might not keep those doors open. Ultimately relationships are what sustain success. I don’t think cockiness is ever good because it has this element to it of I’m better than other people.”

What Makes Us Cocky

Cockiness can come from nature, nurture or success.

A tendency toward confidence—through lack of anxiety—appears partly inborn, says Vancouver, British Columbia-based psychologist Randy Paterson, author of How to Be Miserable: 40 Strategies You Already Use. He cites research by Harvard University psychologist Jerome Kagan, who found that some infants are more easily stressed than others and the difference persisted through adolescence. “We seem to differ in terms of how highly strung we are and our degree of caution,” Paterson says. The least naturally stressed among us might be more likely to underestimate risks and challenges.

Or cockiness might be parented into us.

Wade’s whole family had a healthy sense of self-confidence. “My father told us, ‘Hey, if you believe you can do it, you can do it,’ ” she says. “And in college I learned that the world is your oyster.” So she didn’t question whether she could succeed at whatever she attempted.

And there’s the everybody-gets-a-medal school of child-rearing. “It’s not only having never failed, it’s never having been told that you failed,” Paterson says. “I am a harsh and relentless critic of self-esteem parenting. I’m seeing a tremendous number of young adults who’ve reached young adulthood without ever being told that anything they’ve done is not good enough. There’s grade inflation, and they’ve been coddled in an environment where everyone is constantly telling them how wonderful everything they do is. Then we feel resentful and critical of them for believing it.”

But genuine success can also lead to an inflated ego. Although a poor student, LaPedis’ gift for making money convinced him he was invincible. “I did things I didn’t see other people doing,” he says. “When people keep telling you constantly, ‘You’re amazing. Nobody else has ever done this,’ it is difficult to keep yourself in check. You change.”

Related: How to Keep Your Ego From Getting the Best of You

Feltz says the same is true in sports, where some young athletes take too much credit for their own success, “especially when one is not skilled or experienced enough to know one’s actual ability.”

Changing Your Cocky Ways

Time and life are often natural cures for cockiness.

“It evaporates for many people through their 20s,” Paterson says. “There’s a kind of teenage narcissism that many of us get over when reality smacks us in the eyes.”

LaPedis confidently rode the wave of his success until everything came crashing down in 2008. The economy tanked, properties suddenly stopped selling. His credit cards were maxed out, loans were being called in, and he had cashed in his life insurance policy. “So I wasn’t worth anything dead either.” On top of that, his wife was experiencing a difficult pregnancy.

Then, at 43, he had a major heart attack. And that changed him. “A near-death experience is unlike any other,” he says. “You’re so happy to be alive, and you’re humbled.”

LaPedis’ businesses are robust again, but he has a new attitude toward the work and people in his life—especially his wife. “Back when I thought I could do no wrong; we weren’t a team. But now we are.”

He now has a son on the autism spectrum, and this has also required a new attitude. “He’s really taught me patience. You cannot be cocky. It’s really a good way of learning to treat everyone better.”

Today LaPedis’ wife still sometimes uses gentle teasing to let him know when his ego gets out of hand, and he has learned strategies to keep himself in check—reading and rereading his emails to make sure they won’t be misinterpreted, for example.

Similarly, Wade’s attitude was adjusted by a life-threatening flare-up of her sickle-cell disease. “I started thinking about what kind of legacy I would have left. I became a more patient person; I took it down a couple of notches. And in the past, I would rather fall down a flight of stairs than allow someone to help me. But I thought, What does it say about me if I don’t want people’s help? Allowing people to help you is a humbling experience.” Today she says she’s still confident, but more likely to let others praise her talents rather than doing so herself.

For King, learning how others saw him was the turning point. He started reading books about personality and communication skills. He also admitted his problem to others, which endeared him to them. “As soon as I opened up to say, ‘Hey, I suck at this stuff,’ that was a major changing point,” he says.

He adds, “My business partner is good about saying, ‘Hey, dude, you’re not yourself right now. You need to do a head check and relax and go work from a closet for a while.’ ”

If you would prefer to avoid a near-death experience or devastating evaluation, there are other ways you can assess your own cockiness (see our quiz on Page 70). Of course, Burton cautions, “This requires self-reflection, and the question becomes whether the issues that create cockiness in a person also make it unlikely that they will be self-reflective.” Narcissistic Personality Disorder—which is like cockiness on steroids—is perhaps the least treatable of the personality disorders because true narcissists refuse to consider they might have behavioral problems.

Short of that extreme diagnosis, if you hit roadblocks in your pursuit of goals, feel that others don’t welcome your presence or input, or have been told to rein in your ego, an honest discussion with someone you trust and respect is in order. “Say, ‘Can you give me a very specific example where you saw that showing up?’ ” Burton advises. “And the key is to be quiet. Don’t defend your behavior. It isn’t about beating yourself up. It’s about learning so you can change.”

Kahnweiler suggests recording your phone calls to see whether you talk more than listen and how much you use the word I. “When I was learning coaching, I was given an 80-20 rule—discussions should be 80 percent the client, 20 percent you,” she says. “If you’re talking more [than your client], then you’re not accomplishing your job as a coach.” The same sort of guidelines, she suggests, could help subdue cockiness.

Taming cockiness is a matter of admitting to yourself and others that you don’t know everything. That’s not easy, but it has payoffs.

“The idea of being authentic and making yourself vulnerable to others—it’s scary at first, but so liberating,” King says. “It requires so much emotional and psychic energy to maintain any kind of façade. If you don’t have to hold up any false image of who you are, then you can pour every ounce of energy into your business and family.”

Related: If You Change Yourself, You Can Change Your Life

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.