The walk up to the ring is only a few dozen steps, but it feels like 10 miles. My heart is racing and all of my senses are a blur. I’m vaguely aware of the crowd, several hundred people gathered around to watch, including some of my closest friends and colleagues, but all I can think about is my mouthpiece.

Where is my freaking mouthpiece? I’m about to get punched in the face and I don’t have my mouthpiece. I could lose my teeth. I could get a concussion.

I could actually die.

JOHN TOMAC

That’s what the waiver form cautioned in boldfaced Times New Roman as I signed away my right to legal recourse should something go terribly wrong today when I step into the boxing ring for the very first time—to fight a fellow amateur named J.B. Foote. I meet J.B. only a couple hours before our bout, and I marvel at just how calm he somehow seems. While we wait for our slot on the night’s event schedule, J.B. fields work calls and takes a lot of cigarette breaks. He isn’t the most imposing guy in the world physically, more muscular than I am but shorter. And I know the damage he’s doing to his lungs won’t help him as the fight goes into the later rounds if it lasts that long. But he looks and acts pit-bull tough. He is covered in tattoos, a true guy’s guy. I learn that he works outside with his hands, that he’s a veteran of the Iraq war. He casually peppers in F-bombs as he tells me about the last fight he was in, a street brawl that resulted in emergency surgery to save the other man’s eye. I believe him.

J.B. hasn’t trained for today’s fight, he says, because he’s been fighting all his life.

I, on the other hand, have never been in a fight, unless you count the wrestling moves my middle school friends and I used to pull on one another on the trampoline. I’m a magazine editor who sits at a computer or in meetings all day, wearing loafers. Except, that is, for my hourlong lunch break during which, for months, I’ve been visiting a local boxing gym. At first the routine was meant for exercise and stress relief. The original goal was merely to sweat off a few pounds while taking out my angst on the heavy bag. No one else in my usual noon class was much of a fighter, either. It was mostly filled with guys like me trying to squeeze in a workout on their lunch hour because we were too lazy to wake up early for exercise. Our fellow pugilists were stay-at-home moms who needed the release more than anyone. After a few warm-up calisthenics, a trainer would start to call out punch combinations to get the muscles firing and the heart pumping: “Jab, cross, hook, jab, cross, uppercut, cross.” We would all dance around the bags for 30 minutes with a few water breaks sprinkled in, and I would typically skip the 15-minute ab session at the end so I had time to pick up a kale smoothie on my way back to the office.

It wasn’t bloodlust that led me to take the next step and actually enter the ring. It was something closer to guilt.

When I took over as the editor in chief of SUCCESS in the fall of 2015, I began to challenge our editorial staff to think about our personal- and professional-development content in a different way. Instead of simply writing about it, I wanted us to be about it. I wanted our staffers and freelancers to take on obstacles, demonstrate the process of overcoming them and explain what they learned about themselves and why difficult things are worth doing. Rather than penning a how-to story on perseverance, I tasked our managing editor to train with the world’s greatest endurance athlete. Instead of researching 79 Ways to Project Confidence, I dared our associate editor to try out stand-up comedy and perform in front of a crowd of strangers. I sent a writer out alone, overnight, on one of the country’s most treacherous hiking trails. I made our assistant editor give up her precious iPhone and disconnect from technology for a time.

Their stories were great. Yet I, the leader, hadn’t done anything of the sort. I felt like a fraud. I was pushing the people who worked under me but not pushing myself to show that I had the same level of commitment. So when I heard that a sports talk radio station was set to hold its annual Fight Night event for local wannabe boxers, I felt obligated to sign up.

Related: Afraid of Risks? How to Be Bolder

So here I am, “In the blue corner, standing 6-foot-2, weighing in at 190 pounds and fighting out of Longview, Texas—Josh ‘The Final Boss’ Ellis!”

Round 1

Just before the bell sounds, I get some last words of advice from my ringside trainer appointed by the radio station. “Keep your hands up! Don’t lead with your head! Punch and move!”

I’ve been hearing these same simple commands for weeks. After receiving confirmation that I would be fighting, I enlisted the help of a private trainer at my gym. Like a lot of people who get serious about combat sports, Oreaser “O” Brown III was a troubled kid with a temper and an eye out for bullies. Brown has a fighter’s build, lean through the hips and waist but with an upside-down triangle of a chest, and a thick neck built to take a punch. Every time we face one another to spar, I notice the intensity of his big brown eyes. In our sessions he ratchets up my physical training and walks me through boxing scenarios I wouldn’t experience in a group class—how to attack if my opponent is off-balance, what to do if he starts to crowd me or if I find myself trapped against the ropes. I grow used to the smell of O’s breath.

More helpful than anything, he shares the secrets of a winning mentality. “You don’t step in that ring unless you’re ready for a fight,” Brown tells me. “You gotta have the mindset that I’m fighting for my life, because you might be—you never know. So you come out to fight for your life and don’t quit.”

This isn’t an exaggeration: Around the world there have been hundreds of deaths in boxing over the last century, with many of the fatalities occurring right in the ring. Even wearing padded gloves and protective headgear, I know there is still a possibility that even an unpolished fighter like J.B. can land one terrible punch with just the right force in just the wrong spot.

But as the bell rings to start the fight, my new trainer slides the mouthpiece past my lips, apparently having held it for safekeeping the whole time. A sense of relief washes over me.

The calm evaporates within the first five seconds as J.B. and I meet in the center of the ring. I make a slight head fake, then throw a jab to try to establish myself as a puncher to fear. My opponent sees it coming and casually deflects the straight left hand with both of his gloves. That was too easy for him, I think. We circle one another for a while, each of us looking for an angle, occasionally throwing punches that either miss or are easily blocked.

Jab-cross-hook—blocked-blocked-blocked. Jab-uppercut-jab-cross—blocked-blocked-blocked-blocked. J.B. lands a couple of shots that don’t hurt but keep me off balance. I can’t figure out a way to get to him. I’m frustrated and on the defensive, moving and dodging.

When I watch the video of our fight afterward, I can’t help but compare this dance to the feeling-out process I went through in my first few months running the magazine. I worked to pick my spots for subtle changes here and there, and tried to set a tone for the group, but this was my first time in any management role. I had never been anyone’s boss before. I had read countless articles and books on leadership in my previous years as a more junior editor at SUCCESS. I had been exposed to experts on the subject, such as our columnist, the great author John C. Maxwell, and our own leadership editor, John Addison. Yet bringing the principles of superior people management into real life was as much a puzzle as the defensive strategy of the former Marine standing in front of me now.

Round 2

In the buildup to my fight, I began to see the event as an opportunity to prove I deserved my leadership title. I asked Addison how he did it more than two decades prior, when he had his first management role.

“Titles are nice. But titles don’t make you a leader.”

“Titles are nice,” he told me. “But titles don’t make you a leader. Leadership is about your ability to influence people and get people to work together toward a common cause and to do things that they normally would not do.”

He explained that he realized long ago that you’re never really ready for that first position, no matter how many classes you go to or courses you take. You’re never really ready for being in charge, and everybody reacts to it differently.

“When you step into that first role of leadership, you’ve got to understand there’s a bunch of people who are thinking, Why did that idiot get the job?” he said. “And you’ve got to work hard to win their confidence. You do that by performing, by working hard, by being knowledgeable, by not just being in the room going, ‘Hey, I’m the boss, you all do the work—you all just go do it.’ People aren’t going to follow you just because you’ve got a title. You’ve got to work hard to earn their respect and trust.”

My own leadership self-doubt didn’t stem only from my inexperience as a manager but from my age. I was 29 when I was promoted to lead, among others, a senior editor who had worked in journalism longer than I had been alive and a pair of designers a decade older than me. With open positions to fill on the editorial side, I was hesitant to hire anyone born before me just because I feared the awkward feeling of having to correct their work or explain that they couldn’t take a week off when it would leave us shorthanded.

In recent years, the so-called impostor syndrome has often been written about as an issue for women in the workplace, but as a millennial coming of age in my career, I felt it, too. It wasn’t that I doubted my ability to oversee a great magazine, but that I felt out of place doing so. I was still interested in dinosaurs, the same as when I was 8 years old. How was I going to be anyone’s “boss”?

“That’s a situation that would stoke impostor fears for a lot of people,” says Amy Cuddy, a social psychologist who teaches at Harvard Business School. She’s the author of last year’s best-seller Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges. “You don’t just have power nominally. There are these people under you, and you can be sort of afraid of them.” I suspect that’s part of why some people just don’t want to be a leader or manager to begin with. And so, as a result, they never have the opportunity to develop those leadership skills.

Cuddy says a lot of people are not attributing their accomplishments to something constant or internal, such as talent or ability, but crediting something beyond their control, “like luck or, worst case, favoritism: Someone gave them their job and they didn’t really deserve it.”

For all of my concerns about myself as a leader, I realize by the start of the second round that my impostor syndrome is far more appropriate in the boxing ring. I escaped the first round having taken a few glancing blows and landing no powerful punches of my own, and now my corner man urges me to loosen up.

“Fake it until you make it” is the best advice a lot of people get after earning a promotion. As Round 2 gets underway, that’s basically my approach to boxing. I shake my arms and legs and hop around, partly to stay light on my feet, but mostly because it’s the kind of thing I’ve seen Floyd Mayweather do, and he always wins.

J.B. and I resume the twirling dance, this time with more intensity. We know the time is short to score points with the crowd (whose cheers will decide the winner if there is no knockout) in our three-round bout. Although he’s tough, J.B. isn’t particularly efficient with his movements, and as he falls off-balance, I throw a lucky but powerful right hook that draws a roar from the crowd. That one felt good, I think, the way a perfect drive off the tee feels in golf, a sport I’m far better equipped to play. But rather than take advantage of my momentarily stunned opponent and let the fists fly, I return to dancing around him, unsure of myself even after landing my best punch. Now J.B. just comes back angrier.

JOHN TOMAC

Tired, I lose my fundamentals for a moment, dropping my hands, and although I see my opponent’s wind-up coming from a mile away, I am powerless to stop it, and he lands a crushing overhand right to the temple. That drives me backward and leaves me with a sensation I’ve never had before—hollow-headed—with my hearing muffled and a sense of swelling that feels like my brain is attempting to hatch itself through my cranium.

Through all my training sessions with O, I never actually took a punch; for insurance purposes, the gym’s policy wouldn’t allow it. In this moment, I wish desperately that I had been given a better idea of what to expect, so I wouldn’t be shocked by the intense pain. “It gut-checks you,” O told me of my opponent’s first big blow. “It creates a question of how you’re gonna react. Are you gonna stay in the fight, or are you gonna backpedal, not wanting to get hit?”

In the video of the fight, one of the radio personalities calling the play-by-play describes the look on my face as “failed smile.” It’s not that I’m happy to get punched—it’s that I know I must look like a fool, and I don’t know how else to react. Although completely dazed by J.B.’s right hand, my instincts kick in when he moves in to try to finish the job. He punches wildly, but I slip, move and avoid him, and twice he falls over while trying for the kill shot.

Round 3

Unsure of myself as I was in my earliest months in charge of the magazine, I slowly began to feel more confident as time passed. Issue after issue came out on schedule and in fine shape, and we all settled into a groove. Maybe because I didn’t feel particularly worthy of the “boss” title, I simply treated the people working for me as friends and equals. Occasionally I had to ask them to do this or correct that, but I approached them from a level footing. No matter our individual roles, our accomplishments or our station, I do believe that all people are equal. Hoping that ethos would never leave me, I started getting used to my new job.

“Throughout your career you have to get comfortable being uncomfortable.”

“One of the things that throughout your career you have to do is to get comfortable being uncomfortable,” Addison says. “You’ve got to plow through it. You’ve got to jump in and get better. I believe the key to being great is first you stink, and then you get better than stinking. You’re OK. Then you get better than OK. You become fair. Then you become good. And if you work your ass off, one day you might become great.”

It’s been a year and a half now, and our team is strong. I’ve taken some punches along the way, of course. Nothing’s ever perfect; we’ve had to pull stories and scramble to fill pages at the last minute on a few occasions. We’ve dealt with a budget crunch. Our fantastic senior editor retired in the summer. But we get along great, support one another and do work that we’re all really proud of. Best I can tell, that means I’m doing my job. So who knows whether I’m a great leader or even a fair leader? That’s not really for me to decide.

Related: What Kind of Leader Are You? A Fixer, Fighter or Friend?

With my head still pounding from the huge punch in Round 2, I somehow find a way to upgrade my boxing from stinking to OK before the fight’s final round. When the bell rings, I don’t come out to dance, but to outpunch my opponent. So long as I can avoid a knockdown, I might still have a chance to win the crowd’s favor.

JOHN TOMAC

I score with a straight right hand to J.B.’s chin. Then a hook to his body. I dodge another punch, then connect to the head with a right hook. He tries two jabs, but I deflect them and come back with a two-punch combination.

J.B.’s getting tired, and tries to wrap me up, but I hit him with two quick uppercuts to the body as he gets closer. As the round comes to a close, I feel like I’m winning. I might not have beaten him bloody, but I am less tired than he is. I am the one controlling the fight at the end.

***

“When it comes to impostor fears, I think the first thing we need to recognize is that almost everyone feels them,” Cuddy says. “As opposed to faking it until you make it, I talk about faking it until you become it. Faking it until you make it is kind of putting on a mask so that you can get to where you want to go, and then you’re done. You take the mask off, and you go back to being yourself again or something.”

She says that when people feel like impostors, they are hiding themselves. “They’re actually hiding their best selves, and so it makes it harder for them to not only perform well but to be and feel authentic and present, and to walk away from these challenging situations and feel like they did everything they could do to be their best. And that peace is hugely important.”

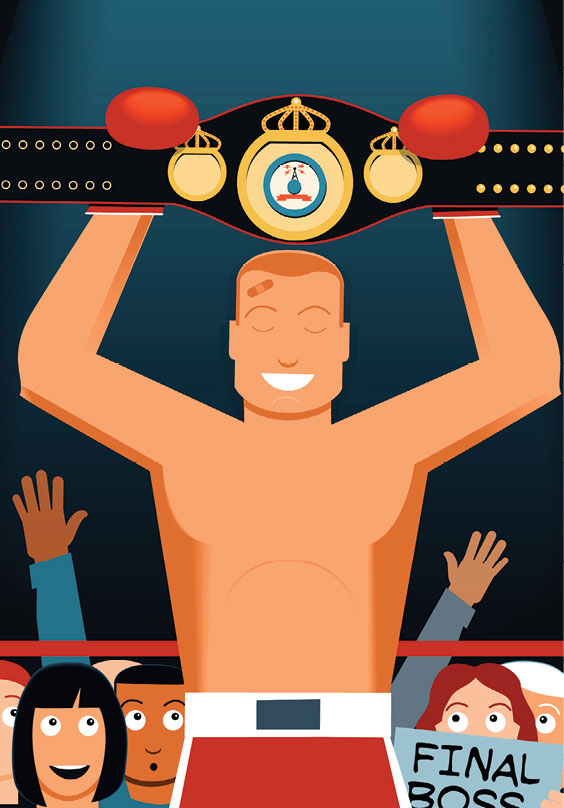

As the ring announcer slides through the ropes, I feel like I’ve become a boxer. Not a great boxer, but a boxer. I boxed. And in a challenging situation, I believe I did everything I could to be my best, which is all I ever ask my team in their work. Appealing to the crowd to decide the winner, the announcer calls J.B.’s name first, and my opponent gets a large ovation.

I don’t know what to expect when my name is called, and his punch from the second round still has my hearing somewhat muffled. But I can still tell… the cheers are just a little louder. I won.

How did that happen? I wonder. Yeah, I was better at the end, but boxing is supposed to be scored round by round. I didn’t feel great about either of the first two rounds. Maybe I was better than I realized. Maybe I should be checked for a concussion.

The referee raises my hand, and a pretty girl in a tight outfit hands over a leather title belt adorned with a colorful pair of boxing gloves on the front and gold-colored plastic on the sides. It reads “Sports Radio 1310 AM/96.7 FM ‘The Ticket’ Fight Night Champion – 2016.”

I wear it all night. I’m proud of what I did, but more proud of the fact that I felt compelled to do it in the first place, that I wanted to lead by putting myself into the fire—just like I’ve asked of my team. I’m proud, too, that so many of them came out to see me fight.

Panting for air as we duck under the ropes, we’re steered over to a long table beside the ring. Neither J.B. nor I realized it at the time, but the crowd’s cheers were only meant for show. Three ringside judges sanctioned by USA Boxing, the sport’s governing body for amateurs, scored the fight, and all three gave the first two rounds to J.B. and the third to me.

Officially, and by unanimous decision, I’ve lost. But the crowd vote means I get to keep the championship belt.

In the end, I didn’t win the belt and the bragging rights because I was the better fighter. I won them because my teammates were there to cheer for me as loudly as they could.

Related: 10 Habits of Ultra-Likeable Leaders

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.