At the Union Square farmers market in New York City, Fredrick Coleman chats with his customers about confit and rillettes. Coleman, 29, works the booth for a farm that raises rare-breed pigs and sells pork to upscale Manhattan restaurants. Between restocking the table and checking eggs for cracks, he explains the differences between kielbasa and bratwurst to discerning New Yorkers. One man, in a wool coat and Burberry scarf, approaches the booth. “This is what I did with the pork shoulder that I got here last week,” he says as he shows Coleman a cellphone photo of his braised entree. A little while later, the fishmonger next to Coleman offers him a piece of thinly sliced raw seafood. “What is it?” he asks after popping it into his mouth. Cod. The two then discuss its texture and suitability for sushi.

Coleman is the quintessential foodie. But just two years earlier he had never even eaten a fresh pea.

That was before he started working for the Brooklyn, New York, nonprofit program Drive Change, which operates a food truck that hires and trains formerly incarcerated youths and young adults in hopes of keeping them out of the justice system for good. As one of their first hires in 2013, six months before Drive Change officially launched, Coleman had notched a total of about two years in holding cells and jail—less than many of the program’s anticipated team members. When he joined, assault charges stemming from a bar fight had been dropped, but not before he had been locked up at Rikers Island correctional facility for a week while awaiting trial.

Related: How to Live Free

Coleman is quite open about his familiarity with his local police station and had spent more than one weekend in a holding cell there. “I was an angry person. I’m not even sure why. I was surrounded by a lot of negativity, and I didn’t know how to be any other way.”

As for his diet, it was an afterthought. The supermarkets in Coleman’s Bronx neighborhood are stocked with produce that “had been on the shelves for God knows how long,” he says, so it was safer to eat processed and frozen foods from the corner deli. Foods such as sushi and organic meats were alien to him, an unaffordable luxury.

When he first heard about Drive Change and its food truck, Coleman wanted no part of it. “I imagined a hot dog and pretzel stand,” he jokes. But the truck, which is called Snowday, is not your average gyro-and-kebab vendor. Part of the gourmet food-truck trend big in cities such as Los Angeles, Washington, Miami, New York and Austin, Texas, Snowday serves sandwiches and sides, all prepared with a maple syrup theme and fresh farm-to-truck ingredients, 90 percent of which are locally sourced. Two of the summer items on Snowday’s ever-changing menu: maple grilled cheese with smoked ham and charred asparagus with pea shoots and maple remoulade.

And for the employees, the job is more than just a fry-guy or dishwasher gig. The “fellows,” as the program calls the young ex-inmates it employs, are trained in every aspect of the business, from cooking to accounting to, yes, dishwashing. The first month on the job, fellows receive hospitality training and work toward obtaining their food-vendor licenses. The next seven months are spent in the prep kitchen in Brooklyn, learning the quirks of fennel, oyster mushrooms and beets, and on the truck—anywhere in the city—interacting and sharing their food with hungry New Yorkers. In addition, they attend six hours a week of professional development, learning about conflict resolution, money management, social media, marketing and small-business development. During the last four months of the program, each participant works another job but continues Drive Change’s professional development classes.

“I don’t just want us to be a job placement service,” explains Drive Change founder Jordyn Lexton, 30. “We are building skills. We want everyone we work with to be capable of being assets wherever they go.”

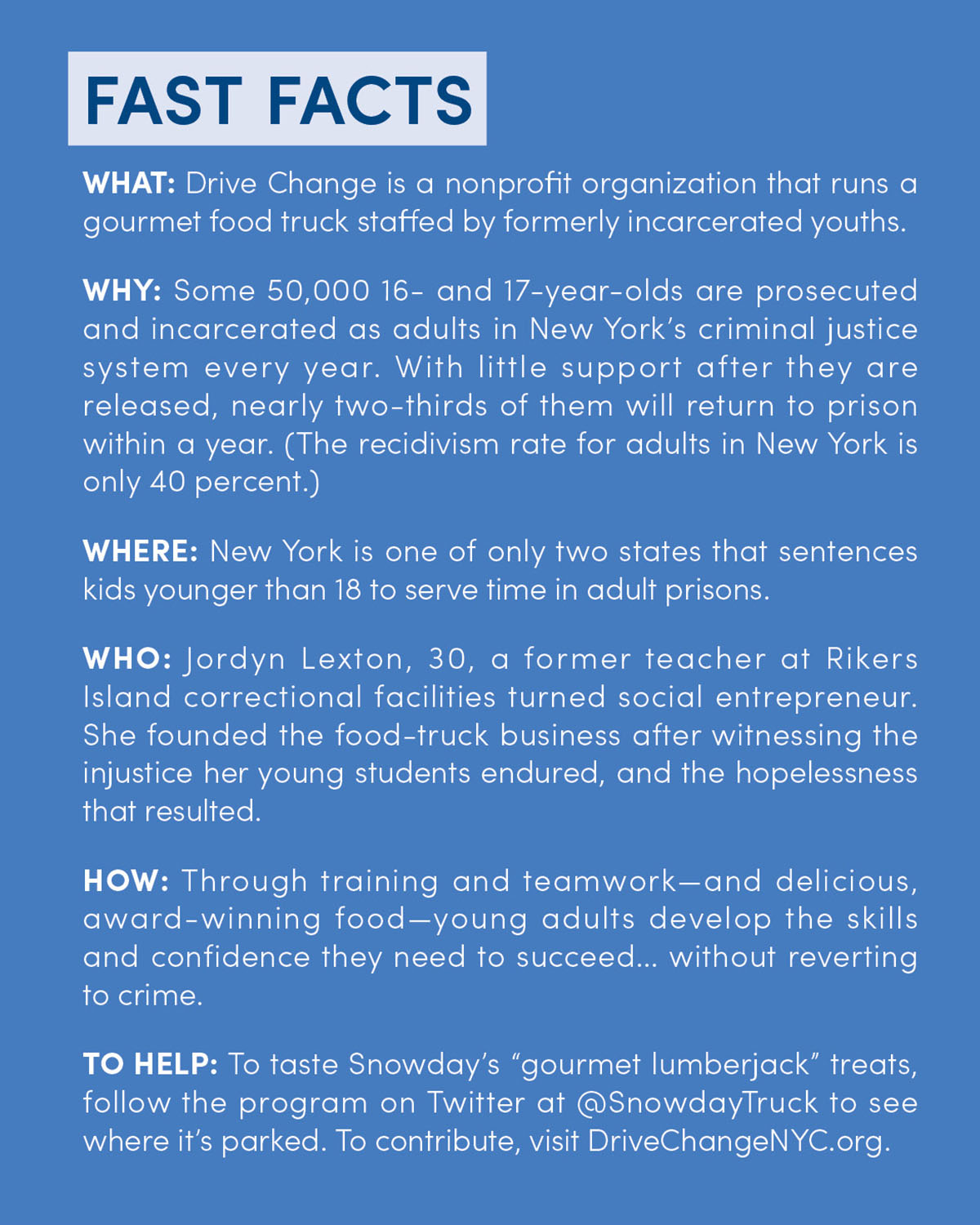

Just as important, she wants to keep them from returning to jail or prison. New York is one of only two states (North Carolina being the other) that automatically prosecutes and incarcerates 16- and 17-year-olds as adults. That means that a kid who just turned 16—imagine a sophomore in high school, struggling with geometry and biology—can be sent to Rikers Island, one of the most violent correctional facilities in the country. Youths in adult prisons face the highest risk of sexual abuse, according to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service. They are more likely to report being beaten by staff, and they’re 36 times more likely to commit suicide in an adult prison than if they’re housed in a juvenile detention facility.

Some hard-liners may argue that if 16-year-olds are mature enough to, say, sell drugs, then they are mature enough to serve out their punishment in an adult prison. But all measures show that incarcerating youths only makes them more likely to commit more—and often worse—crimes. Because once their time is up, these kids have trouble reconnecting with family, finishing school, finding employment, and getting the help they may need for underlying mental health issues or substance abuse. As a result, a distressing 63 percent of youth offenders return to prison within a year after release, according to the New York State Office of Children and Family Services.

***

Lexton has seen this catch-and-release cycle personally. A former teacher at Rikers, the first stop for most offenders in New York City, she taught adolescent men awaiting trial. Over the course of three years, she watched as more than half of her students returned to the dingy, makeshift classroom in a trailer where she worked. “The place was soul-crushing,” she says. “There was so much anxiety and fear.” The one time her students perked up was during a culinary arts class. “They took pride in preparing food that other people enjoyed.”

At age 26, Lexton left her job at Rikers and vowed to find a way to use food to better help the kids. “I was looking for something that capitalized on their culinary interest, allowed for employment, and lent itself to urban skill-building,” she says. Food trucks fit the bill. What’s more, the truck could serve as a sort of mobile mission statement, spreading the word about what she calls the “truly devastating” effects of youth incarceration. Despite having no previous culinary experience, Lexton began raising money on the crowdfunding website Indiegogo.com and applying for government grants while she apprenticed for seven months as a manager on a Korean taco truck.

A distressing 63 percent of youth offenders return to prison within a year after release.

She credits her mom and dad for helping her financially through the transition. And that’s part of the reason she chose the path of social entrepreneurship. Unlike Coleman, Lexton did grow up eating fresh fruits, vegetables and worldview-expanding foods like sushi. “I traveled the world with my parents and ate amazing food everywhere I went.” She grew up on Manhattan’s posh Upper East Side, attended an elite private school (Dalton) and then a top college (Wesleyan, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts in English), and “had access to everything.”

But Lexton doesn’t take her good fortune for granted. “The difference between my experience as a young adult, when I had every door open for me, and the young men I taught was so stark. The doors were just being shut on them, one after another, at such an early age.”

Snowday aims to open a door.

The truck, a revamped On Star utility truck decorated with wood repurposed from water tanks destroyed by 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, opened for business in April 2014. Since then it has parked at street fairs, festivals, outdoor markets and events around the state. Its goal, Lexton says, is to “serve delicious, inspired meals with a side of social justice.”

The money that Snowday makes—around $200,000 a year—goes toward the fellows’ salaries and the truck’s operating costs.

***

Vidal Guzman, like Coleman, was an early participant in the program. Locked up for the first time at age 16, Guzman came home when he was 17, only to return to jail at 19. He remained there for five more years. Guzman is polite, soft-spoken and matter-of-fact as he explains why he spent the majority of his young adulthood behind bars: “I was young and stupid and ran around with the wrong crowd.”

There’s more to Guzman’s story, however. Like so many young people who become entangled in the criminal justice system, he was raised by a single mother who struggled to put food on the table. “We were homeless sometimes,” he says. Wanting to help his mom with money, he followed the example of many kids in his Harlem neighborhood—including his older brother, incarcerated since 2002—who were selling drugs as well as robbing neighbors and local businesses. Although his mother had set a positive example, Guzman says “it hurts me that I went out and started learning from other people.”

In prison, Guzman was surrounded by hopeless men who were in for 25-to-life. “People were getting cut, fighting, jumping other inmates. I saw my friends die. I didn’t want to think that this was how life was.” But as terrible as it was, he says, “everybody’s afraid to come home.” So was he. “People end up falling into the same things they already know. I didn’t want to fear being successful.”

Nevertheless, when he was released at 24, he was penniless. Even with help from the Getting Out and Staying Out (GOSO) re-entry program, Guzman repeatedly was turned down when he applied for jobs. “I was close to selling drugs again, but they [GOSO staff] told me to stay patient.” His patience paid off when he interviewed with Drive Change.

He loved the job: “Everything about it. Every day [at work] was like another day I could enjoy.” Being a part of a team that was positive had a marked effect on him. “A lot of my friends from when I was a kid have been killed. But my friends now are growing up. I want people around me who keep me motivated and are doing things with their lives.” People like Lexton? “Yes, she is an amazing person. I hope everyone tells her that. We teach each other and motivate each other.

“I don’t regret being in jail,” Guzman is able to say now. “I appreciate what God had for me. It could have been worse.… I could have been killed. It’s the past now, and I have to work on the future.” To that end, since finishing his year with Drive Change, he has been working at a Brooklyn bakery. His long-term plan, though, is to become a personal trainer. “Ten years down the line, I want to start a program like Drive Change that can help people like me.”

***

Although Guzman’s childhood narrative is common among youth offenders, it’s not the only one. Jaquial Jackson, another Drive Change fellow in the pilot program, didn’t grow up in poverty. He lived with his mom and dad in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn. “Everyone thinks of Bed-Stuy as a bad neighborhood, but not where we lived. We were fine.” His parents had stable jobs: His mother is an administrative aide with the New York Police Department, and his father is a manager at FedEx. None of his friends were messing around with drugs or getting into trouble in the streets.

“I just made a really bad decision. I became addicted to the idea of making money and started selling drugs,” Jackson says. “I was 14 years old and making a ton of cash. I thought I had it made.” He was caught at age 15 and sent to a behavioral modification center for seven months. He stayed out of trouble for 10 years before he lost his job with Access-A-Ride, a New York transportation service for the disabled and elderly. “I immediately reverted back to what I knew as a child. I had a 7-year-old son and bills and rent to pay. I made the same wrong decision twice, and I won’t make it again.”

When Jackson was released from prison a year later, he got in touch with Drive Change because he had always harbored a dream of being a chef. Within months, he was promoted to kitchen manager. “I loved going to the urban farms, meeting the farmers and shopping at the farmers markets.”

“The best way to break a boundary between two people or two cultures is through food,” Jackson says. “When people step up to the truck and taste great food, it starts a conversation.” Drive Change takes advantage of the communal nature of a tasty meal to spread its message about youth incarceration and justice reform.

Food can also be an indicator of economic and social inequality. After all, it’s no secret that in poor areas, it’s much easier to come by a glazed doughnut than a fresh cucumber. Only 8 percent of black Americans live in a community with one or more grocery stores, compared to 31 percent of whites, according to a State of Obesity report from the nonprofit Trust for America’s Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The lack of access to quality food has major consequences for the poor, who are disproportionately black and Latino. Diet-related diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer and heart disease affect these populations on a larger scale than other Americans. Blacks become ill at younger ages and die sooner than their white counterparts, and they die from heart disease at twice the rate of whites.

“Food falls around racial lines,” says Jared Spafford, the culinary director for Drive Change.

Spafford, 30, was a chef at a Brooklyn butcher shop before joining forces with Lexton. His job was a coveted one, but Spafford was frustrated. “I wanted to do more than cook for wealthy people. I couldn’t believe how prohibitively expensive good food, grown and prepared well, was. It seemed really unfair.” He met Lexton at the farmers market, the same one where Coleman now works, and was instantly on board. “It’s a real passion project for me,” Spafford says. “I didn’t know so much about criminal justice reform [before meeting Lexton], but I did know that I wanted to help take away the exclusivity when it comes to eating well.”

Drive Change is just one example of a burgeoning food and social justice movement that aims to redress inequities in the food system. Urban farms—reclaimed patches of land tucked between buildings or atop roofs or on plots within state parkland—are another. And urban farms in New York City have taken a shine to Drive Change. “We have similar missions,” says Nick Storrs, the urban farm manager at the Randall’s Island Park Alliance in New York City. His farm is an educational one where schoolchildren learn where food comes from and are introduced to fare they may have never tried before. For instance, this past growing season, kids sampled tatsoi, a mustardy Asian salad green. “We try to instill a consciousness about how choices about our food affect our health and environment,” Storrs says. Visiting students then prepare farm-fresh meals for each other.

“The best way to break a boundary between two people or two cultures is through food.”

But the kids can’t eat it all. “We are always looking for places to donate our surplus to,” Storrs says. In addition to food pantries, the farm gives much of its excess produce—beets, cucumbers, baby greens and lots of onions—to Drive Change. In fact, most of the food that Spafford and his team whip up aboard Snowday is donated from urban farms. Drive Change fellows visit the farms, too, so that “when they are in the food truck, they can really connect the food to their customers,” Storrs says.

***

And the food is delicious. Lexton was in Canada sampling sugar on snow, which is hot maple syrup poured over shaved ice or packed snow, when she got the idea for the maple syrup-themed cuisine that has been affectionately called “gourmet lumberjack.” Snowday is known for its maple grilled-cheese sandwich, which has an addictively crackly sweet crust and a melty cheddar center.

Because Drive Change fellows never know what ingredients will be donated, they have to be creative on the fly—think rice and rye berry salad in the summer and succotash in the fall. “We didn’t just want to be a crappy pizza shop,” Spafford says. “We wanted the fellows to have real pride in what they were making and selling.” That’s why one of Drive Change’s first priorities was to focus on the menu and gain respect as a serious eatery for serious foodies. Spafford and Lexton didn’t want anyone patronizing the truck out of charity.

Snowday succeeded. In 2014 it won its first Vendy Award—a street-food competition that sells thousands of tickets every summer and chooses the best street eats from hundreds of vendors—for Rookie of the Year. In 2015 Snowday won Vendys as the best food truck and the people’s choice, the first time in Vendy Awards’ 11-year history that the same truck has taken both honors.

***

Drive Change fellows mostly are unequivocal success stories. Besides his weekend gig at the farmers market, Coleman is a line cook at a fashionable Brooklyn restaurant called Reynard, where he slow-roasts lamb ribs and plates liver mousse with pickled vegetables. He has let go of the anger he had growing up, too. “Drive Change and everyone who worked there was just so positive. It’s hard not to see the world positively now.”

Guzman is gainfully employed and on his way to becoming a trainer. Of the 15 fellows who were in Drive Change’s pilot program, 10 made it through to the end and are employed or attending college. “I don’t see prison again in my future,” Guzman says.

Jackson works for New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority as a train conductor, a union job through which he hopes to save enough money to launch his own culinary venture—a passion for channeling the drive and motivation he showed as a 14-year-old.

Drive Change is going places, too. The organization plans to accept 16 new fellows in its “living classroom” this year, and it’s also investing in a new part of the mobile vendor business: a commissary, a lot where food trucks can restock and clean up during their off hours. Running a commissary would offer more employment opportunities for formerly incarcerated youths and unite other vendors around their cause of healthy, accessible food for all. Jackson, for one, is ready to volunteer to get it off the ground: “I would do anything for Jordyn [Lexton]. I love her like a sister. Most people are all about a buck, but she really cares.”

Guzman concurs. “Some people can help open your eyes to the good.”

Related: You Are Filled With Extraordinary Potential

This article originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine.